<p><span style="font-size: 11pt;">Beyond reason</span><br></p><p><span style="font-size: 11pt;"><br></span></p><p><span style="font-size: 11pt;">저산소 환경의 암세포</span></p><p><span style="font-size: 15px; line-height: 23px;">hypoxia inducible factor(HIF) - 단백질</span></p><p><span style="font-size: 15px; line-height: 23px;"><br></span></p><p><span style="font-size: 11pt;"><br></span></p><p><span style="font-size: 11pt;"><br></span></p><p><br></p><p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://t1.daumcdn.net/cfile/cafe/993FAF4F5E02B84029" class="txc-image" actualwidth="863" hspace="1" vspace="1" border="0" width="863" exif="{}" data-filename="스크린샷 2019-12-25 오전 10.15.11.png" style="clear:none;float:none;" id="A_993FAF4F5E02B8402985F2"/></p><p><br></p><p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://t1.daumcdn.net/cfile/cafe/99ADC5475E02B8F725" class="txc-image" actualwidth="881" hspace="1" vspace="1" border="0" width="881" exif="{}" data-filename="스크린샷 2019-12-25 오전 10.18.01.png" style="clear:none;float:none;" id="A_99ADC5475E02B8F725F98F"/></p><p><span style="font-size: 11pt;"><br></span></p><p><b style="font-family: Helvetica; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; text-align: justify; text-indent: -28.2px;">1. 논문명과 저자정보&nbsp;</b></p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 40.2px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -39.3px; font-size: 15px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;"><span style="font-size: 14px;">&nbsp; ㅇ 논문명 : </span>Methylation-dependent Regulation of HIF-1α Stability Restricts Retinal and Tumour Angiogenesis</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35px; font-size: 15px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;"><span style="font-size: 14px;">&nbsp; ㅇ 저자정보 : </span>백성희 교수 (교신 저자, 서울대 생명과학부), 김윤호 박사 (공동 제1저자, 서울대 생명과학부), 남혜진 연구교수 (공동 제1저자, 서울대 생명과학부)&nbsp;</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35px; font-size: 10px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica; min-height: 12px;"><b></b><br></p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 29.1px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -28.2px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;"><b>&nbsp;2. 연구의 필요성&nbsp;</b></p>

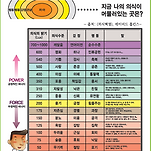

<p style="margin-top: 5px; margin-left: 33.2px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.2px; font-size: 15px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp;&nbsp; <span style="font-size: 14px;">ㅇ</span><b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);"> 암세포는 빠르게 분열하고 성장하므로, 고형 종양 내부에는 혈관이 부족하게 되어 필연적으로 저산소 환경에 놓이게 된다</span></b>. 이러한 <b><span style="color: rgb(9, 0, 255);">저산소 환경에서는 히프원(Hypoxia inducible factor 1)</span><span style="color: rgb(9, 0, 255);">&nbsp;단백질의 발현이 증가되어 암세포가 증식하는데 도움을 주는 역할</span></b>을 하게 된다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 5px; margin-left: 37.9px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -39.9px; font-size: 15px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; <span style="font-size: 14px;">ㅇ <b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">히</span></b></span><b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">프원 단백질은 혈관 형성을 촉진하여 암세포가 혈관으로부터 산소를 잘 공급받을 수 있게 한다</span></b>. 또한, <b><span style="color: rgb(9, 0, 255);">암세포의 대사 작용을 변화시키는 것</span></b>으로 알려져 있다. <b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">저산소 환경의 암세포는 TCA 회로를 통한 에너지 공급이 아닌 산소를 사용하지 않는 해당작용만으로 충분히 에너지를 공급받을 수 있도록 대사 작용을 바꾸는데, 이 과정에서 히프원 단백질이 중요한 역할</span></b>을 한다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 5px; margin-left: 33.3px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.3px; font-size: 15px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; <span style="font-size: 14px;">ㅇ </span><b><span style="color: rgb(9, 0, 255);">히프원 단백질은 저산소 환경에서만 특징적으로 발현이 유도되는데, 이 단백질의 발현을 조절하는 새로운 기전이 있을 것으로 예상하였고 그 기전을 찾는다면 새로운 암 치료제를 개발하는 데에 응용될 수 있을 것으로 착안하여 본 연구를 진행</span></b>하였다.&nbsp;</p>

<p style="margin-top: 5px; margin-left: 27.9px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -27.9px; font-size: 15px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica; min-height: 18px;"><br></p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 29.1px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -28.2px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;"><b>&nbsp;3. 연구배경</b></p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 35.3px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -34.4px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ 저산소 환경은 여러 생리적 상황과 질병 상황에서 유도된다. 특히 <b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">고형 종양에서 저산소 환경이 유도된다</span></b>는 것이 잘 밝혀져 있다.&nbsp;</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 35.3px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -34.4px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ <b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">저산소 환경에서는 세포가 정상적으로 에너지를 생성하지 못하기 때문에, 산소의 이용률을 높이기 위한 여러 반응이 세포에서 일어난</span></b>다. <b><span style="color: rgb(9, 0, 255);">HIF-1α라는 전사인자는 저산소 상황에서 발현이 증가되어 타깃 유전자의 활성을 유도하는데, HIF-1α는 당 대사 조절, 혈관 생성 등과 관련된 유전자의 발현을 주로 조절</span></b>하는 것으로 알려져 있다.&nbsp;</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 35.3px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -34.4px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ <b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">암이 빠르게 성장하면서 주변 환경이 저산소 환경으로 변화되는데, 이때 유도된 HIF-1α는 암세포 주변의 혈관 형성에 중요한 역할을 하여 암의 성장과 증식에 중요한 역할</span></b>을 하는 것이 잘 알려져 있다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 35.3px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -34.4px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ HIF-1α는 암세포의 대사 작용을 변화시키는 것으로 알려져 있다. 저산소 환경의 암세포는 TCA 회로를 통한 에너지 공급이 아닌 산소를 사용하지 않는 해당 작용만으로 충분히 에너지를 공급받을 수 있도록 대사 작용을 바꾸는데, 이 때 HIF-1α가 중요한 역할을 한다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 35.3px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -34.4px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica; min-height: 17px;"><br></p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 29.1px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -28.2px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;"><b>&nbsp;4. 연구내용</b></p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36.8px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.9px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ 본 연구에서는 <b><span style="color: rgb(0, 85, 255);">HIF-1α 단백질의 안정화를 조절하는 새로운 기전으로서 메틸화</span></b>를 밝혔다. 단백질의 번역후 변형과정의 일종인 메틸화에 의해 HIF-1α 단백질의 안정성이 조절되는 기전을 새롭게 제시하였다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36.8px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.9px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ HIF-1α의 아미노산 서열을 분석한 결과, SET7/9 메틸화 효소에 의해 인지될 수 있는 타깃 아미노산 서열이 리신 32번기에 있는 것을 확인하고, LC-MS/MS 분석을 통하여 그 리신 잔기에서 메틸화가 일어나는 것을 확인하였다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36.8px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.9px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ 실제로 SET7/9 효소에 의해서 리신 32번기에 HIF-1α의 메틸화가 일어나는 것을 다양한 실험을 통해 확인하였다. 또한 HIF-1α와 결합하는 단백질 복합체 분석을 통하여 <b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">HIF-1α의 새로운 결합 단백질로서 LSD1이라는 탈메틸화 효소를 찾아냈고, 이 LSD1이 SET7/9에 의한 HIF-1α의 메틸화를 반대로 탈메틸화 하는 것을 확인</span></b>하였다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36.8px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.9px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ HIF-1α의 메틸화의 기능을 확인하기 위하여, <b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">저산소 환경에서 시간에 따른 HIF-1α의 메틸화 정도를 확인한 결과, 정상 상태의 산소 농도에서는 HIF-1α의 단백질 발현이 낮은 반면 HIF-1α의 메틸화 정도는 높은 것을 확인</span></b>하였다. 즉,<b><span style="color: rgb(9, 0, 255);"> HIF-1α의 메틸화 정도가 HIF-1α의 단백질 발현양과는 반대의 상관관계를 가지고 있는 것을 확인</span></b>하였다. 이를 통하여 HIF-1α의 메틸화가 일어나면 단백질 분해가 촉진되어서 단백질이 불안정화 된다는 것을 규명하였다.&nbsp;</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36.8px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.9px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ 탈메틸화 효소인 LSD1의 유전자 결손 마우스로부터 제작한 MEF (mouse embryonic fibroblast) 세포주에서 HIF-1α 단백질이 불안정화 되어있고, 여기에 LSD1을 다시 발현시키자 HIF-1α 단백질이 다시 안정화 되는 것을 확인하였다. 하지만 LSD1의 효소적 기능이 없는 돌연변이체는 HIF-1α단백질을 안정화 시키지 못했다. 이를 통하여 LSD1이 탈메틸화 효소 기능을 이용하여 HIF-1α 단백질의 안정화에 기여하는 것을 확인하였다. 또한 pargyline이라는 LSD1 효소 활성 억제제를 사용한 경우에 HIF-1α가 불안정화 되었다. 이를 통하여 <b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">메틸화를 조절하면 HIF-1α 단백질의 발현양을 능동적으로 조절할 수 있다는 사실을 증명</span></b>하였다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36.8px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.9px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ 세포주를 이용한 실험뿐만 아니라 생체 내에서 HIF-1α 메틸화의 기능을 규명하기 위하여 메틸화가 일어나는 리신 32번기를 알라닌으로 교체한 <i>Hif-1a<sup>KA/KA</sup></i> knockin 쥐를 제작하였다. 이 쥐는 HIF-1α의 메틸화가 전혀 일어나지 않으므로 HIF-1α 단백질이 매우 안정화되어 발현양이 높아진 것을 확인하였다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36.8px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.9px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ <b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">HIF-1α는 혈관 형성에 중요한 역할을 하므로 </span><i><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">Hif-1a</span><sup><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">KA/KA</span></sup></i><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);"> knockin 쥐에서 혈관 생성 여부를 확인한 결과, 대조군에 비하여 혈관이 더 많이 생성된 것을 확인</span></b>하였다. 또한 <i>Hif-1a<sup>KA/KA</sup></i> knockin 쥐의 경우 대조군에 비하여 종양의 크기도 더 크고, 종양 주위에 혈관도 더 많이 형성된 것을 확인하였다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36.8px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.9px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ 흥미롭게도 암환자에서 발견되는 HIF-1α의 돌연변이를 살펴 본 결과 HIF-1α의 메틸화가 일어나는 리신 32번의 아미노산 주변에서 의미있는 수준의 돌연변이를 발견하였다. 그 중 세린 28번과 아르기닌 30번잔기에 돌연변이가 일어난 암환자의 경우에는 특히 HIF-1α의 메틸화와 연관성이 깊은 것을 확인하였다. 리신 32번의 주변 아미노산의 돌연변이로 인하여 HIF-1α의 메틸화가 일어나지 못하게 되므로, 리신 32번기 돌연변이와 유사하게 HIF-1α가 안정화 된다는 기전을 밝혔다.&nbsp;</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 36.8px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -35.9px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica; min-height: 17px;"><br></p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 29.1px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -28.2px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;"><b>5. 발견원리</b></p>

<p style="margin-top: 5px; margin-left: 32.7px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -34.7px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ 연구팀은 히프원 단백질의 발현을 조절하는 새로운 기전으로 메틸화에 의한 조절이 있을 것으로 예상하였고 히프원 단백질의 메틸화가 32번째 리신 아미노산 잔기에 SET7/9 메틸화 효소에 의하여 일어나는 것을 확인하였다. 또한, 히프원 단백질의 메틸화는 LSD1이라는 탈메틸화 효소에 의하여 감소되는 것을 확인하였다.&nbsp;</p>

<p style="margin-top: 5px; margin-left: 41px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -43px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ 히프원 단백질의 메틸화는 저산소 환경에서는 LSD1의 발현이 증가하여 히프원 단백질의 탈메틸화를 유도하여 단백질을 안정화 시키는 것을 확인하였다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 5px; margin-left: 36.1px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -38.1px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ 연구팀은 히프원 단백질의 메틸화가 일어나지 않는 돌연변이 쥐를 제작하여 생체 내에서 암 발생 및 혈관 생성 기능을 확인하였다. 그 결과, 안정화된 히프원 단백질에 의하여 종양의 크기가 커지고 혈관이 대조군에 비하여 더 많이 생성된 것을 확인하였다.&nbsp;</p>

<p style="margin-top: 5px; margin-left: 36.1px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -38.1px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica; min-height: 17px;"><br></p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 29.1px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -28.2px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;"><b>6. 기대효과</b></p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 35.2px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -34.3px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; <span style="font-size: 15px;">ㅇ</span> HIF-1α 단백질의 안정화에 기여하는 메틸화라는 새로운 기전을 밝힘으로서 메틸화 조절을 통한 새로운 암 치료법을 제시할 수 있을 것으로 기대된다.</p>

<p style="margin-top: 10px; margin-left: 35.2px; text-align: justify; text-indent: -34.3px; font-size: 14px; line-height: normal; font-family: Helvetica;">&nbsp; ㅇ<b><span style="color: rgb(9, 0, 255);"> LSD1 탈메틸화 효소가 암세포에서 과발현 되어 있는 것이 밝혀져 있었는데, 이렇게 과발현된 LSD1이 HIF-1α를 탈메틸화 시켜 안정화에 기여함으로써 암세포 증식과 성장에 중요한 역할</span></b>을 한다는 것을 밝혀냈다. 이를 통하여 LSD1을 타깃으로 하는 약물이 암 세포 억제에 중요한 역할을 할 수 있다는 것을 제시하고 있다.&nbsp;</p>