Books of The Times | 'Rebel in Chief' and 'Impostor'

Disparate Conservative Assessments of

Bush

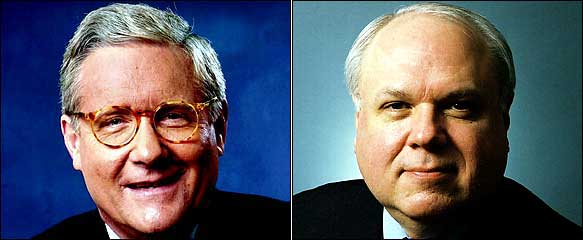

Left: Fox News Channel; Right: Van Riper Photography

Left: Fred Barnes; Right: Bruce Bartlett.

REBEL IN CHIEF

Inside the Bold and Controversial

Presidency of George W. Bush

By FRED BARNES

220 pages. Crown

Forum. $23.95.

IMPOSTOR

How George W. Bush Bankrupted America

and Betrayed the Reagan Legacy

By BRUCE BARTLETT

310 pages.

Doubleday. $26.

Published: February 21, 2006

The portraits of President George W. Bush served up by these two new books could

not be more at odds.

Both authors are die-hard, dyed-in-the-wool conservatives. Bruce Bartlett

("Impostor"), former executive director of the Joint Economic Committee of

Congress, worked in the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush and wrote the 1981 supply-side

manifesto "Reaganomics." Fred Barnes is executive editor of "The Weekly

Standard" and a co-host of the Fox News program "The Beltway Boys." The two

authors, however, have come to diametrically opposing views of the current

president.

Mr. Barnes views Mr. Bush as "a president who leads," an action-oriented

"visionary," an executive who combines "F.D.R.'s cool optimism" and Teddy

Roosevelt's "pugnacity and determination." Mr. Barnes had unusual access to

members of the press-phobic administration: he interviewed Mr. Bush as well as

Vice President Dick Cheney, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld for this volume. But he did not use

this access to ask hard-hitting questions. Instead, his book echoes the

administration's own portrayals of itself, even employing the same sort of macho

adjectives the White House and Bush campaigns have used to characterize the

president: "bold," "audacious," "steadfast," "unflinching."

As Mr. Barnes sees it, Mr. Bush's brand of conservatism — activist,

forward-leaning and willing to use the government to solve problems — is "the

conservatism of the future."

Mr. Bartlett, in contrast, sees Mr. Bush as a "pretend conservative" — "a

partisan Republican, anxious to improve the fortunes of his party" but

"perfectly willing to jettison conservative principles at a moment's notice to

achieve that goal." He writes that the current White House is "obsessive about

secrecy," argues that Mr. Bush has pursued "what could be described as a

Nixonian agenda using Nixon's methods" and declares that when it comes to the

federal budget, "Clinton was much better." Mr. Bush, he contends, has set the

country on "an unsustainable fiscal course," resulting in a ballooning deficit

that will inevitably lead to tax increases.

As Mr. Bartlett sees it, "the 2002 collapse of Enron" — the giant energy

trading company, which "borrowed heavily, paid little in taxes, and made big

profits in ways that were known to be contrary to sound business practices" —

"may in some ways be a metaphor for the Bush Administration's economic

policy."

His critique extends well beyond the economic sphere. He argues that "Bush

has driven away and even humiliated the few intellectuals in his midst,

preferring instead the company of overrated political hacks whose main skills

seem to be an ability to say yes to whatever he says and to ignore the obvious."

And he declares that the president's "unwillingness to properly utilize the

traditional policy development process" lies "at the heart of the failure of his

Social Security proposal and possibly the Iraq operation as well."

"One of the hallmarks of George W. Bush's approach to policy that is

disturbing both to friends and foes alike," Mr. Bartlett writes, "is an apparent

disdain for serious thought and research to develop his policy initiatives.

Often they seem born from a kind of immaculate conception, with no mother or

father to claim parentage."

Mr. Bartlett argues that the failure of "the administration to chart or

articulate a consistent economic policy" stemmed, in large measure, from "Bush's

disinterest in serious policy analysis" and his sidelining of people with

genuine expertise. He writes that Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill and his successor, John Snow, were treated

as "little more than errand boys," and that the Council of Economic Advisers was

accorded little influence as well. It became clear, Mr. Bartlett writes, that

the main job of the Council's chairman, R. Glenn Hubbard, "was not to devise

economic policies, but only to offer support for those Bush had already decided

upon."

These remarks by Mr. Bartlett echo earlier observations about the

administration's mistrust of experts and often haphazard decision-making

process, made by journalists like George Packer (writing about the Iraq war) and

former administration insiders. Richard A. Clarke, the former counterterrorism adviser,

has written that on issues like terrorism and Iraq, "Bush and his inner circle

had no real interest in complicated analyses; on the issues that they cared

about, they already knew the answers, it was received wisdom." Former Treasury

Secretary Paul O'Neill once told Vice President Cheney that he felt

administration members needed to bring more "analytical rigor, sound

information-gathering techniques and real, cost-benefit analysis" to the

decision making process. And John DiIulio, the former head of the Bush

administration's faith-based initiative, wrote a 2002 memo to the reporter Ron

Suskind, in which he lamented that "in eight months, I heard many, many staff

discussions but not three meaningful, substantive policy discussions."

The descriptions of the Bush White House in "Rebel-in-Chief" do not exactly

contradict those in "Impostor," but where Mr. Bartlett sees slapdash

decision-making, Mr. Barnes sees decisiveness and visionary leadership — an

admirable contempt for "small ball" and a practical desire to focus on results,

not means. Mr. Barnes seems to think that being "a risk taker" who "loves to

smash conventional wisdom" is a positive thing in a president, and he points out

that Mr. Bush "hates to manage a problem or a dispute or a broken relationship,"

preferring to cut to "what's the solution?"

The account that Mr. Barnes gives of the president's approach to

speech-making is especially telling, ironically ratifying Mr. Bartlett's

observation that Mr. Bush likes to spurn traditional policy-making channels.

In "Rebel-in-Chief," Mr. Barnes writes that Mr. Bush "has used his

presidential speeches to advance policies far beyond where his aides expected

him to go," that "rather than reflect policy, his speeches dictate policy."

Typically, he notes, the Bush speechwriting process begins with a meeting

between the president and Michael Gerson, his former chief speechwriter turned

policy adviser. Once drafted, the speech is circulated at the White House but

"is not open to debate."

"This is the first time most White House and administration officials see a

speech," Mr. Barnes writes. "It already has the president's imprimatur. Advisers

are free to recommend a change in wording, but Bush does not tolerate attempts

to alter the general direction of a speech."

In the case of the second Inaugural Address, which declared that spreading

liberty around the world was "the calling of our time," Mr. Barnes reports that

Mr. Bush teased Condoleezza Rice, saying "You're not going to believe what I

say." Ms. Rice reportedly responded, "I hope I get to see it before you give

it." What she and other senior Bush advisers later saw, Mr. Barnes goes on, "was

a near-final draft to which only minor changes could be made." He continues, The

thrust of the speech — the new direction, the policy declaration — had been

set."

Not only does Mr. Barnes fail to make a persuasive case for the virtues of

Mr. Bush's go-it-alone management style, but his narrative is also so replete

with blinkered predictions, ridiculous generalizations and absurdly rosy

pronouncements as to undermine any trust whatsoever in the author. He writes

that "America's strategic position has indeed been fortified" by the president's

Middle East policy, that "Afghanistan and Iraq are pro-American democracies"

now, and that "Bush had received vindication both abroad and at home" when

Iraqis turned out to vote in last year's elections — as if that meant that the

war had been deemed successful and wise.

Mr. Barnes assails the press for contending that Mr. Bush has "indulged in

more God-talk than his predecessors" (he contends that Bill Clinton "mentioned Jesus Christ more than Bush

has"), even though Mr. Barnes himself writes that "Bush has been more powerfully

affected by his faith than any other president" and that his "faith has had an

enormous impact on his policies." He says "the Bush approach to foreign policy

and key domestic issues, and his use of government, will stick as key elements

of the conservatism of the future," despite the president's low standing in the

polls, despite the public's unhappiness with the war in Iraq, despite many

conservatives' worries about his administration's lavish spending ways. And he

writes that "President Bush revealed his proactive tendencies after Hurricane

Katrina devastated New Orleans and coastal Mississippi in the late summer of

2005," despite the fact that Mr. Bush and the federal government were painfully

slow to respond to the emergency, as a scathing report issued by House

Republicans noted a week ago.

As for Mr. Bartlett's book, there is one gaping omission: a reluctance to

grapple with the huge federal deficits run up by his hero, Ronald Reagan. But

while this omission blunts the author's complaints about President Bush's

deficit spending, it does not detract from his larger criticisms of the current

administration: namely, its subversion of many traditional conservative beliefs

(like a wariness of Wilsonian efforts to export democracy and a wariness of big

government); its willingness to subordinate long-term policy goals to short-term

political gains; and perhaps most important, its distrust of the government's

traditional policy-making apparatus and its inclination to make decisions based

on ideology and grand ideas rather than on substantive analysis and debate.

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/21/books/review/21kaku.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1&th&emc=th

|