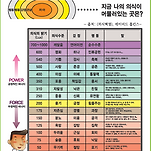

<p><span style="font-size: 11pt;">BEYOND REASON</span><br></p><p><span style="font-size: 11pt;"><br></span></p><p><span style="font-size: 11pt;">진정한 치유는 기쁨, 감사, 축복 540 치유의 에너지장에서 시작된다</span></p><p><br></p><p><span style="font-size: 15px; line-height: 23px;">슬프고도 슬픈 이야기</span></p><p><span style="font-size: 15px; line-height: 23px;">'아주 가까운 지인이 항우울제를 처방받고 결국 자살을 선택했다. 수많은 논문에서 항우울제는 자살의 위험성을 높이기 때문에 주의해야 한다고 말하지만 의사들은 오늘도 자신이 배운대로&nbsp;항우울제를 처방할 뿐이다. 우리는 어떻게 자신과 가족, 동료들을 이 위험성에서 구해낼 수 있을까?'</span></p><p><span style="font-size: 15px; line-height: 23px;"><br></span></p><p><span style="font-size: 15px;">'무기력, 절망감과 함께 오는 우울증일때 항우울제를 복용하면 욕망이라는 에너지 장에 올라가면서 자신의 생명을 끊을 수 있는 힘이 생긴다는 이야기'</span></p><p><span style="font-size: 15px;"><br></span></p><p><span style="font-size: 15px;"><b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);"></span><a href="http://cafe.daum.net/panicbird/S3Cq/113" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer" class="tx-link"><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">클릭클릭 - 우울증의 비타민, 미네랄, 보충제 치료법!!</span></a><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);"></span></b></span></p><p><span style="font-size: 11pt;"><br></span></p><p><br></p><p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://t1.daumcdn.net/cfile/cafe/99EA2F335DF42AE11C" class="txc-image" actualwidth="736" hspace="1" vspace="1" border="0" width="736" exif="{}" data-filename="스크린샷 2019-12-14 오전 9.18.16.png" style="clear:none;float:none;" id="A_99EA2F335DF42AE11C0D16"/></p><p><span style="font-size: 11pt;"><br></span></p><p><span style="font-size: 11pt;"><br></span></p><div class="jig-ncbiinpagenav" data-jigconfig="smoothScroll: false, allHeadingLevels: ['h2'], headingExclude: ':hidden'" id="ui-ncbiinpagenav-1" style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0); font-family: 'Times New Roman', stixgeneral, serif; font-size: 16px; line-height: 21px; background-color: rgb(255, 255, 255);"><div class="fm-sec half_rhythm no_top_margin" style="margin: 0px 0px 0.6923em; font-size: 0.8425em; line-height: 1.6363em; font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif;"><div class="fm-citation half_rhythm no_top_margin clearfix" style="margin: 0px 0px 0.6923em; zoom: 1;"><div class="inline_block eight_col va_top" style="max-width: 100%; vertical-align: top; display: inline-block; zoom: 1; width: 452.3125px;"><div><span class="cit"><span role="menubar"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" role="menuitem" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">J R Soc Med</a></span>. 2016 Oct; 109(10): 381&#8211;392.&nbsp;</span></div><div><span class="fm-vol-iss-date">Published online 2016 Oct 11.&nbsp;</span><span class="doi" style="white-space: nowrap;">doi:&nbsp;<a href="https://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F0141076816666805" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CFront%20Matter&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CCrosslink%7CDOI" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">10.1177/0141076816666805</a></span></div></div><div class="inline_block four_col va_top show-overflow align_right" style="max-width: 100%; vertical-align: top; text-align: right; display: inline-block; zoom: 1; width: 222.703125px;"><div class="fm-citation-ids"><div class="fm-citation-pmcid"><span class="fm-citation-ids-label">PMCID:&nbsp;</span>PMC5066537</div><div class="fm-citation-pmid">PMID:&nbsp;<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27729596" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">27729596</a></div></div></div></div><h1 class="content-title" style="font-size: 1.5384em; margin: 1em 0px 0.5em; line-height: 1.35em; font-weight: normal;">Precursors to suicidality and violence on antidepressants: systematic review of trials in adult healthy volunteers</h1><div class="half_rhythm" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;"><div class="contrib-group fm-author"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Bielefeldt%20A%26%23x000d8%3B%5BAuthor%5D&amp;cauthor=true&amp;cauthor_uid=27729596" class="affpopup" co-rid="_co_idm140000952946688" co-class="co-affbox" style="white-space: nowrap; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Andreas Ø Bielefeldt</a>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">1</span>&nbsp;<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Danborg%20PB%5BAuthor%5D&amp;cauthor=true&amp;cauthor_uid=27729596" class="affpopup" co-rid="_co_idm140000970312128" co-class="co-affbox" style="white-space: nowrap; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Pia B Danborg</a>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">1,</span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">2</span>&nbsp;and&nbsp;&nbsp;<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=G%26%23x000f8%3Btzsche%20PC%5BAuthor%5D&amp;cauthor=true&amp;cauthor_uid=27729596" class="affpopup" co-rid="_co_idm140000974135840" co-class="co-affbox" style="white-space: nowrap; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Peter C Gøtzsche</a><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><img src="https://img1.daumcdn.net/relay/cafe/original/?fname=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov%2Fcorehtml%2Fpmc%2Fpmcgifs%2Fcorrauth.gif" alt="corresponding author" style="max-width: 100%; border: 0px;"></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">1</span></div></div><div class="fm-panel half_rhythm" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;"><div class="togglers"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" class="pmctoggle" rid="idm140000953265200_ai" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Author information</a>&nbsp;<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" class="pmctoggle" rid="idm140000953265200_cpl" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Copyright and License information</a>&nbsp;<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/about/disclaimer/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Disclaimer</a></div><div class="fm-article-notes fm-panel half_rhythm" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;"></div></div><div id="pmclinksbox" class="links-box whole_rhythm" style="border: 1px solid rgb(234, 195, 175); background-color: rgb(255, 244, 206); padding: 0.3923em 0.6923em; margin: 1.3846em 0px; border-top-left-radius: 5px; border-top-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-left-radius: 5px;"><div class="fm-panel">This article has been&nbsp;<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/citedby/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">cited by</a>&nbsp;other articles in PMC.</div></div></div><div class="sec" style="clear: both;"></div><div id="idm140000957682784" lang="en" class="tsec sec" style="clear: both;"><div class="goto jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-container" style="float: right; text-align: right; font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-size: 0.86666em !important;"><span role="menubar"><a class="tgt_dark page-toc-label jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-heading" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" title="Go to other sections in this page" role="menuitem" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="background-image: url(https://static.pubmed.gov/portal/portal3rc.fcgi/4160049/img/2846531); background-color: transparent; padding-right: 17px; margin-right: 3px; color: rgb(100, 42, 143); background-position: 100% 43.5%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat;">Go to:</a></span></div><h2 class="head no_bottom_margin ui-helper-clearfix" id="idm140000957682784title" style="font-size: 1.125em; line-height: 1.1111em; margin: 1.125em 0px 0px; color: rgb(152, 87, 53); min-height: 0px; border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(151, 176, 200); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Abstract</h2><div><div id="__sec1" class="sec sec-first" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="__sec1title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Objective</h3><p id="__p1" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;"><b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">To quantify the risk of suicidality and violence when selective serotonin and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are given to adult healthy volunteers with no signs of a mental disorder</span></b>.</p></div><div id="__sec2" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="__sec2title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Design</h3><p id="__p2" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;"><b><span style="color: rgb(0, 85, 255);">Systematic review and meta-analysis.</span></b></p></div><div id="__sec3" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="__sec3title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Main outcome measure</h3><p id="__p3" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Harms related to suicidality, hostility, activation events, psychotic events and mood disturbances.</p></div><div id="__sec4" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="__sec4title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Setting</h3><p id="__p4" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Published trials identified by searching PubMed and Embase and clinical study reports obtained from the European and UK drug regulators.</p></div><div id="__sec5" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="__sec5title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Participants</h3><p id="__p5" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in adult healthy volunteers that reported on suicidality or violence or precursor events to suicidality or violence.</p></div><div id="__sec6" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="__sec6title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Results</h3><p id="__p6" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A total of 5787 publications were screened and 130 trials fulfilled our inclusion criteria. The trials were generally uninformative; 97 trials did not report the randomisation method, 75 trials did not report any discontinuations and 63 trials did not report any adverse events or lack thereof. Eleven of the 130 published trials and two of 29 clinical study reports we received from the regulatory agencies presented data for our meta-analysis. Treatment of adult healthy volunteers with antidepressants doubled their risk of harms related to suicidality and violence, odds ratio 1.85 (95% confidence interval 1.11 to 3.08,&nbsp;<em>p</em>&#8201;=&#8201;0.02, I<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">2&#8201;</span>=&#8201;18%). The number needed to treat to harm one healthy person was 16 (95% confidence interval 8 to 100; Mantel-Haenszel risk difference 0.06). There can be little doubt that we underestimated the harms of antidepressants, as we only had access to the published articles for 11 of our 13 trials.</p></div><div id="__sec7" class="sec sec-last" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="__sec7title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Conclusions</h3><p id="__p7" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;"><b><span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);">Antidepressants double the occurrence of events in adult healthy volunteers that can lead to suicide and violence.</span></b></p></div></div><div class="sec" style="clear: both;"><strong class="kwd-title">Keywords:&nbsp;</strong><span class="kwd-text">Psychiatry, antidepressants, depression, healthy volunteers</span></div></div><div id="sec1-0141076816666805" class="tsec sec" style="clear: both;"><div class="goto jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-container" style="float: right; text-align: right; font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-size: 0.86666em !important;"><a class="tgt_dark page-toc-label jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-heading" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" title="Go to other sections in this page" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="background-image: url(https://static.pubmed.gov/portal/portal3rc.fcgi/4160049/img/2846531); background-color: transparent; padding-right: 17px; margin-right: 3px; color: rgb(100, 42, 143); background-position: 100% 43.5%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat;">Go to:</a></div><h2 class="head no_bottom_margin ui-helper-clearfix" id="sec1-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1.125em; line-height: 1.1111em; margin: 1.125em 0px 0px; color: rgb(152, 87, 53); min-height: 0px; border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(151, 176, 200); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Introduction</h2><p id="__p8" class="p p-first" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">The reporting of harms in drug trials is generally poor, with inadequate explanation of how they were collected, and often harms are missing altogether.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr1-0141076816666805" rid="bibr1-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597975" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">1</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr2-0141076816666805" rid="bibr2-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_585007451" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">2</a></span></span>&nbsp;From 2011 to 2012, the Nordic Cochrane Centre received unredacted clinical study reports on antidepressants filed for regulatory approval at the European Medicines Agency and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. We demonstrated selective reporting of major harms in the published articles of duloxetine and inconsistencies between the protocols and the clinical study reports.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr3-0141076816666805" rid="bibr3-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597982" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">3</a></span></span>&nbsp;Furthermore, we noticed that the adverse events tables in clinical study reports had hidden suicidal events due to the medical dictionaries and coding conventions used.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr4-0141076816666805" rid="bibr4-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597991" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">4</a></span></span>Based on the 70 clinical study reports we received, we found that antidepressants more than doubled the risk of suicidal and aggressive behaviour in children and adolescents.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr5-0141076816666805" rid="bibr5-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597985" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">5</a></span></span></p><p id="__p9" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A 2012 systematic review of 33 trials in healthy volunteers documented various effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors but only mentioned the adverse events in a few words.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr6-0141076816666805" rid="bibr6-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597995" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">6</a></span></span>&nbsp;The review was based on published articles and none of these lived fully up to the CONSORT guideline for good reporting.</p><p id="__p10" class="p p-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Since their introduction in the late 1980s, the benefits and harms of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors have been the subject of huge debate. Because their harms &#8211; in particular suicidality &#8211; have often been explained away as if they were disease symptoms or only a problem in children,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr7-0141076816666805" rid="bibr7-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">7</a></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr8-0141076816666805" rid="bibr8-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr9-0141076816666805" rid="bibr9-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a></span>&#8211;<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr10-0141076816666805" rid="bibr10-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">10</a></span></span>&nbsp;we wished to quantify the risk of suicidality and violence when these drugs are given to adult healthy volunteers.</p></div><div id="sec2-0141076816666805" class="tsec sec" style="clear: both;"><div class="goto jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-container" style="float: right; text-align: right; font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-size: 0.86666em !important;"><a class="tgt_dark page-toc-label jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-heading" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" title="Go to other sections in this page" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="background-image: url(https://static.pubmed.gov/portal/portal3rc.fcgi/4160049/img/2846531); background-color: transparent; padding-right: 17px; margin-right: 3px; color: rgb(100, 42, 143); background-position: 100% 43.5%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat;">Go to:</a></div><h2 class="head no_bottom_margin ui-helper-clearfix" id="sec2-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1.125em; line-height: 1.1111em; margin: 1.125em 0px 0px; color: rgb(152, 87, 53); min-height: 0px; border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(151, 176, 200); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Methods</h2><p id="__p11" class="p p-first" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">According to our prespecified protocol (available from the authors), we included double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (called antidepressants throughout this paper) in adult healthy volunteers with no signs of a mental disorder. There were no language restrictions. We excluded trials in abusers of tobacco, drugs or alcohol and also imaging studies, as these have another objective and furthermore are of poor methodological quality.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr11-0141076816666805" rid="bibr11-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597972" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">11</a></span></span></p><p id="__p12" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">We searched PubMed (1966 to December 2015) and Embase (1974 to December 2015) using the search strings specified in&nbsp;<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/table/table1-0141076816666805/" target="table" class="fig-table-link figpopup" rid-figpopup="table1-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-table1-0141076816666805" co-legend-rid="" style="display: inline-block !important; zoom: 1 !important; cursor: pointer; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Table 1</a>. The searches were conducted in collaboration with an information specialist to ensure the inclusion of drugs that were not indexed in PubMed’s MeSH thesaurus. One researcher (AØB) screened all search results by reading titles and abstracts, and all excluded studies were rescreened by the same researcher who also read the included studies and extracted relevant trial data, e.g. design, population size, harms, discontinuations and funding, to a spreadsheet. A second researcher (PBD) extracted data on a randomly selected sample of 30 articles; as there were no discrepancies, we did not perform data extraction in duplicate.</p><div class="table-wrap table anchored whole_rhythm" id="table1-0141076816666805" style="clear: both; margin: 1.3846em 0px; background-color: rgb(255, 252, 240); border: 1px solid rgb(234, 195, 175); border-top-left-radius: 5px; border-top-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-left-radius: 5px; padding: 1.3846em;"><h3 style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Table 1.</h3><div class="caption"><p id="__p13" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Search strings for PubMed and Embase.</p></div><div data-largeobj="" data-largeobj-link-rid="largeobj_idm140000971662160" class="xtable" style="clear: both; max-height: 80vh; overflow: auto;"><table frame="hsides" rules="groups" class="rendered small default_table" style="clear: both; border-collapse: collapse; border-spacing: 0px; margin: 1.3846em 0px; font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; border-top-width: 1px; border-top-style: solid; border-top-color: rgb(0, 0, 0); border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><thead align="left" valign="top" style="border: none;"><tr><th rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="text-align: center; background-color: inherit; padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Database</th><th rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="text-align: center; background-color: inherit; padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Search string entered</th></tr></thead><tbody align="left" valign="top" style="border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(136, 136, 136); border-top-width: 1px; border-top-style: solid; border-top-color: rgb(136, 136, 136);"><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">PubMed</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">(“Healthy Volunteers”[Mesh] OR Healthy OR Normal) AND (“atomoxetine”[Supplementary Concept] OR “reboxetine”[Supplementary Concept] OR “O-desmethylvenlafaxine”[Supplementary Concept] OR “clovoxamine”[Supplementary Concept] OR “Serotonin Uptake Inhibitors”[Pharmacological Action])</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="5" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Embase</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 exp serotonin uptake inhibitor/</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">2 exp serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor/</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">3 1 or 2</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">4 normal human</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">5 3 and 4</td></tr></tbody></table></div></div><p id="__p14" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">We also included relevant clinical study reports on antidepressant drugs we received from regulatory agencies for our projects in this area.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr3-0141076816666805" rid="bibr3-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597980" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">3</a></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr4-0141076816666805" rid="bibr4-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597986" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a></span>&#8211;<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr5-0141076816666805" rid="bibr5-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597966" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">5</a></span></span>&nbsp;We checked whether the clinical study reports had been published by searching for investigator names and drugs on PubMed and Embase.</p><p id="__p15" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">We defined harms as adverse events that were either suicidality or violence or were considered precursor events to suicidality or violence in the literature, with a particular focus on the list of criteria used by the Food and Drug Administration for its 2006 meta-analysis of suicidality in 100,000 patients (<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/table/table2-0141076816666805/" target="table" class="fig-table-link figpopup" rid-figpopup="table2-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-table2-0141076816666805" co-legend-rid="" style="display: inline-block !important; zoom: 1 !important; cursor: pointer; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Table 2</a>).<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr12-0141076816666805" rid="bibr12-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597969" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">12</a></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr13-0141076816666805" rid="bibr13-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr14-0141076816666805" rid="bibr14-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597992" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr15-0141076816666805" rid="bibr15-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597964" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr16-0141076816666805" rid="bibr16-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597988" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr17-0141076816666805" rid="bibr17-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a></span>&#8211;<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr18-0141076816666805" rid="bibr18-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597976" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">18</a></span></span>We categorised the harms as suicidality, violence, activation events, psychotic events and mood disturbances.</p><div class="table-wrap table anchored whole_rhythm" id="table2-0141076816666805" style="clear: both; margin: 1.3846em 0px; background-color: rgb(255, 252, 240); border: 1px solid rgb(234, 195, 175); border-top-left-radius: 5px; border-top-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-left-radius: 5px; padding: 1.3846em;"><h3 style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Table 2.</h3><div class="caption"><p id="__p16" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Types of harms looked for when reading the reports.</p></div><div data-largeobj="" data-largeobj-link-rid="largeobj_idm140001041305024" class="xtable" style="clear: both; max-height: 80vh; overflow: auto;"><table frame="hsides" rules="groups" class="rendered small default_table" style="clear: both; border-collapse: collapse; border-spacing: 0px; margin: 1.3846em 0px; font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; border-top-width: 1px; border-top-style: solid; border-top-color: rgb(0, 0, 0); border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><tbody align="left" valign="top"><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Suicidality</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Core event</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Accident, asphyxia, attempt, burn, cut, drown, firearm, gas, gun, hanged, immolation, injury, jump, monoxide, mutilate, overdose, poison, self-damage, self-harm, self-inflicted, self-injury, shoot, suicide, suffocate</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Potential event</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">&#8211;</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Violence</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Core event</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Antisocial behaviour, assaultive behaviour, criminal behaviour, homicidal ideation, homicide, physical abuse, physical assault, physically threatening behaviour, violence-related symptom</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Potential event</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">&#8211;</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Activation events</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Core event</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Aggression, agitation, akathisia, amphetamine speed-like response, anxiety, anxiety attack, argumentative, caffeine feeling, CNS stimulation, euphoria, excessive energy, feeling euphoric, fidgetiness, frustration, hostility, hyperactivity, hyperkinesia, hypomania (also listed as psychotic event), increased agitation, increased anxiety, increased energy, increased irritability, inner shakiness, irritability, jitteriness, jittery, mania (also listed as psychotic event), motor restlessness, nervousness, overanxious, overstimulation, racing thoughts, restless, restlessness, shakiness, skin crawling, unusual energy</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Potential event</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Easily startled, panic, panic attack, panic symptoms, tenseness, tension, tension increased, trembling, tremor, unable to relax</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Psychotic events</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Core event</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Abnormal feelings, abnormal thinking, behavioural dyscontrol, confusion, delirium, delusions, disorientation, feelings of doom, hallucinations, hypomania (also listed as activation event), hysteria, incoherent thoughts, intrusive thoughts, mania (also listed as activation event), paranoia, psychosis, unusual thoughts</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Potential event</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Abnormal dreams, bad dreams, increased dreams, intense dreams, nightmares, strange dreams, vivid dreams</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Emotional disturbances</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Core event</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Anhedonic, apathy, depersonalisation, derealisation, disinhibition, emotionally detached, emotional lability, feeling blank, flat effect, flattened, impulsivity, indifference, lack of empathy, reduced ability to feel positive emotions, spaciness</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Potential event</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">&#8211;</td></tr></tbody></table></div><div id="largeobj_idm140001041305024" class="largeobj-link align_right" style="margin-top: 0.692em; text-align: right;"><a target="object" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/table/table2-0141076816666805/?report=objectonly" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Open in a separate window</a></div></div><p id="__p17" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Uncertainties during data extraction were resolved by discussion between the authors. If the reporting of harms was unclear, we contacted the authors of the trials for clarification. We assessed the risk of bias in the trials focusing on randomisation and blinding.</p><p id="__p18" class="p p-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">We performed a meta-analysis calculating Peto’s odds ratio for dichotomous outcomes with Review Manager. Because of the considerable risk of carryover effects in crossover trials, we only used trials that reported on periods separately.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr19-0141076816666805" rid="bibr19-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">19</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr20-0141076816666805" rid="bibr20-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597983" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">20</a></span></span></p></div><div id="sec3-0141076816666805" class="tsec sec" style="clear: both;"><div class="goto jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-container" style="float: right; text-align: right; font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-size: 0.86666em !important;"><a class="tgt_dark page-toc-label jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-heading" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" title="Go to other sections in this page" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="background-image: url(https://static.pubmed.gov/portal/portal3rc.fcgi/4160049/img/2846531); background-color: transparent; padding-right: 17px; margin-right: 3px; color: rgb(100, 42, 143); background-position: 100% 43.5%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat;">Go to:</a></div><h2 class="head no_bottom_margin ui-helper-clearfix" id="sec3-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1.125em; line-height: 1.1111em; margin: 1.125em 0px 0px; color: rgb(152, 87, 53); min-height: 0px; border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(151, 176, 200); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Results</h2><p id="__p19" class="p p-first" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">We identified 5787 publications in PubMed and Embase, removed 569 duplicate entries, and screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining 5218 records, which left 316 articles for full-text reading (<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig1-0141076816666805/" target="figure" class="fig-table-link figpopup" rid-figpopup="fig1-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-fig1-0141076816666805" co-legend-rid="lgnd_fig1-0141076816666805" style="display: inline-block !important; zoom: 1 !important; cursor: pointer; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Figure 1</a>).</p><div class="fig iconblock whole_rhythm clearfix" id="fig1-0141076816666805" co-legend-rid="lgnd_fig1-0141076816666805" style="clear: both; margin: 1.3846em 0px; zoom: 1; overflow: hidden; background-color: rgb(255, 252, 240); border: 1px solid rgb(234, 195, 175); border-top-left-radius: 5px; border-top-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-left-radius: 5px; padding: 1.3846em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig1-0141076816666805/" target="figure" rid-figpopup="fig1-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-fig1-0141076816666805" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a><div data-largeobj="" data-largeobj-link-rid="largeobj_idm140000959340096" class="figure" style="text-align: center; max-height: 80vh; overflow: auto; margin: 0px 0px 1.3846em; padding-top: 12px; padding-right: 12px;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig1-0141076816666805/" target="figure" rid-figpopup="fig1-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-fig1-0141076816666805" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a><a class="inline_block ts_canvas" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/core/lw/2.0/html/tileshop_pmc/tileshop_pmc_inline.html?title=Click%20on%20image%20to%20zoom&amp;p=PMC3&amp;id=5066537_10.1177_0141076816666805-fig1.jpg" target="tileshopwindow" style="max-width: 100%; border: none; display: inline-block; zoom: 1; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"><div class="ts_bar small" title="Click on image to zoom" style="background-color: rgb(220, 240, 244); max-width: 100%; margin: auto; position: relative; height: 0px; padding: 0px; color: transparent; font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em;"></div><img alt="An external file that holds a picture, illustration, etc. Object name is 10.1177_0141076816666805-fig1.jpg" title="Click on image to zoom" class="tileshop" src="https://img1.daumcdn.net/relay/cafe/original/?fname=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov%2Fpmc%2Farticles%2FPMC5066537%2Fbin%2F10.1177_0141076816666805-fig1.jpg" style="max-width: 100%; border: 0px; cursor: url(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/corehtml/pmc/css/cursors/zoomin.cur), pointer;"></a></div><div id="largeobj_idm140000959340096" class="largeobj-link align_right" style="margin-top: 0.692em; text-align: right;"><a target="object" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig1-0141076816666805/?report=objectonly" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Open in a separate window</a></div><div class="icnblk_cntnt" id="lgnd_fig1-0141076816666805" style="color: rgb(102, 102, 102); font-size: 0.9em; line-height: 1.5277; display: table-cell; vertical-align: top;"><div style="margin-top: 0px;"><a class="figpopup" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig1-0141076816666805/" target="figure" rid-figpopup="fig1-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-fig1-0141076816666805" style="display: inline-block !important; zoom: 1 !important; cursor: pointer; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Figure 1.</a></div><div class="caption" style="margin-bottom: 0px;"><p id="__p20" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">PRISMA flow diagram of included studies based on the literature searches.</p></div></div></div><p id="__p21" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">We excluded 174 of these articles because the studies were crossover trials using antidepressant inhibitor, a placebo and a third drug, or because the studies were parallel trials that used a drug other than an antidepressant as an interaction drug. This left 142 articles on a total of 130 trials that fulfilled our inclusion criteria, 52 of which were two-period crossover trials. Ten different antidepressants were tested in the trials; citalopram (<em>n</em>&#8201;=&#8201;33) and paroxetine (<em>n</em>&#8201;=&#8201;27) were most commonly used.</p><p id="__p22" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">The trials did not report much about their methodology. All 130 trials were allegedly randomised, but 97 (75%) did not describe the method and 75 (58%) did not report any discontinuations or lack thereof.</p><p id="__p23" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Reporting of adverse events was generally inadequate; 63 trials (48%) did not report any adverse events or stated that there were none; 43 trials (33%) reported at least one adverse event; while 24 trials (18%) reported only the most frequently occurring adverse events or those leading to discontinuation. The source of funding was industry in 29 trials (22%), non-industrial sources in 47 trials (36%), mixed in 17 trials (13%) and not reported in 37 trials (28%).</p><p id="__p24" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Thirteen of the 130 trials reported on at least one of our predefined harms, 10 of which were parallel group trials and three crossover trials. We could not include two of the crossover trials, as there were no data for each period separately. We included the first period of the third crossover trial, which ended prematurely due to carryover effects despite a four-week washout period.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A1</span></p><p id="__p25" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">We received 29 clinical study reports from the regulatory agencies, two of which fulfilled our inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis. None of them had been published. Most of the remaining clinical study reports described non-blinded bioavailability studies or drug interaction studies.</p><p id="__p26" class="p" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Thus, we included 11 trials from our literature searches<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A1&#8211;A11</span>&nbsp;and two from the regulatory agencies<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A12,A13</span>&nbsp;in our meta-analysis. The drugs were citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline or venlafaxine, in all cases given orally. Four trials were not industry sponsored and did not have industry employees among the authors.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A2,A3,A5,A7</span>&nbsp;Trial characteristics, length of treatment and our predefined harms with reported severity are shown in&nbsp;<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/table/table3-0141076816666805/" target="table" class="fig-table-link figpopup" rid-figpopup="table3-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-table3-0141076816666805" co-legend-rid="" style="display: inline-block !important; zoom: 1 !important; cursor: pointer; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Table 3</a>. The harms we found all occurred within the randomised phase of the trials, not during the withdrawal phase after the trials were finished. The median age was 30 years; 40% of the volunteers were women, and the median publication year was 2008.</p><div class="table-wrap table anchored whole_rhythm" id="table3-0141076816666805" style="clear: both; margin: 1.3846em 0px; background-color: rgb(255, 252, 240); border: 1px solid rgb(234, 195, 175); border-top-left-radius: 5px; border-top-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-left-radius: 5px; padding: 1.3846em;"><h3 style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Table 3.</h3><div class="caption"><p id="__p27" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Harms in the meta-analysed trials. Some trials included arms with drugs that were not antidepressants; these data are not shown.</p></div><div data-largeobj="" data-largeobj-link-rid="largeobj_idm140000973613984" class="xtable" style="clear: both; max-height: 80vh; overflow: auto;"><table frame="hsides" rules="groups" class="rendered small default_table" style="clear: both; border-collapse: collapse; border-spacing: 0px; margin: 1.3846em 0px; font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; border-top-width: 1px; border-top-style: solid; border-top-color: rgb(0, 0, 0); border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><thead align="left" valign="top" style="border: none;"><tr><th rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="text-align: center; background-color: inherit; padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Study</th><th rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="text-align: center; background-color: inherit; padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Study design</th><th rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="text-align: center; background-color: inherit; padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Sex and age</th><th rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="text-align: center; background-color: inherit; padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Drug, dosage, length of treatment</th><th rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="text-align: center; background-color: inherit; padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Number of volunteers</th><th rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="text-align: center; background-color: inherit; padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Harms of interest in antidepressant group</th><th rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="text-align: center; background-color: inherit; padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Harms of interest in placebo group</th></tr></thead><tbody align="left" valign="top" style="border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(136, 136, 136); border-top-width: 1px; border-top-style: solid; border-top-color: rgb(136, 136, 136);"><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Almeida (2010)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A2</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Based on 18 completers: Male: 18 Mean age, citalopram: 27.8 years (no range). Mean age, placebo: 26.7 years (no range).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">20&#8201;mg citalopram, 28 days</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Citalopram: 10 Placebo: 10</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 (agitation)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Briscoe (2008)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A3</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Male: 10. Female 10. Mean age: 29 years (20&#8211;44).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">20&#8211;80&#8201;mg fluoxetine, 56 days</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Fluoxetine: 14 Placebo: 6</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 (vivid dreams)</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Carpenter (2011)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A4</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Male: 8. Female: 13. Mean age, sertraline: 30.2 years (20&#8211;46). Mean age, placebo: 28.7 years (20&#8211;54).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">50&#8211;100&#8201;mg sertraline, 42 days</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Sertraline: 11 Placebo: 11</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 (severe nightmares)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Chial (2003)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A5</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Based on 39 completers: Male: 23. Female: 16. Mean age, venlafaxine: 28.8 years (no range). Mean age, placebo: 31.1 years (no range).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">150&#8201;mg venlafaxine, 1 day</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Venlafaxine: 20 Placebo: 20</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 (jittery)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Furlan (2001)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A6</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Based on 49 completers: Male: 27. Female: 22. Mean age, paroxetine: 75.1 years (no range). Mean age, sertraline: 70.7 years (no range). Mean age, placebo: 70.3 years (no range).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">10&#8211;40&#8201;mg paroxetine, 21 days; 50&#8211;150&#8201;mg sertraline, 21 days</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Paroxetine: 18 Sertraline: 16 Placebo: 20</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Sertraline: 1 (nervousness)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Garcia-Leal (2010)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A7</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Male: 43. Mean age: 23.6 years (19&#8211;31).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">10&#8201;mg or 20&#8201;mg escitalopram, 1&#8201;day</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Escitalopram: 31 Placebo: 12</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 (anxious, on 10&#8201;mg)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Knorr (2011)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A8</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Male: 50. Female: 28. Mean age: 32 years (no range).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">10&#8201;mg escitalopram, 28 days</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Escitalopram: 39 Placebo: 39</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">6 (restlessness) 1 (tremor)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">9 (restlessness) 1 (tremor)</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Levine (1987)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A9</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Male: 14. Female: 106. Mean age, fluoxetine: 43 years (no range). Mean age, placebo: 46 years (no range).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">20&#8211;80&#8201;mg fluoxetine, 56 days</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Fluoxetine: 60 Placebo: 60</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">4 (anxiety) 4 (depression) 7 (nervousness) 3 (tremor)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">5 (anxiety) 1 (depression) 2 (nervousness)</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Madeo (2008)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A10</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Male: 48. Mean age, citalopram: 31.1 years (no range). Mean age, fluoxetine: 29.2 years (no range). Mean age, placebo: 29.2 years (no range).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">20&#8211;40&#8201;mg citalopram, 31 days; 20&#8201;mg fluoxetine, 31 days</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Citalopram: 16 Fluoxetine: 16 Placebo: 16</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 (anxiety, on fluoxetine)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;"></td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Montejo (2015)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A11</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">No gender data. Mean age, escitalopram: 24.1 years (no range). Mean age, placebo: 23.0 years (no range).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">20&#8201;mg escitalopram, 63 days</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Escitalopram: 36 Placebo: 32</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">4 (abnormal dreams) 1 (agitation and tremor) 1 (anxiety)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">2 (abnormal dreams)</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Pijl (1991)<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A1</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Crossover study, converted to parallel study by trialists due to carryover effects</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Female: 23. Mean age, fluoxetine: 38.1 years (25&#8211;53). Mean age, placebo: 37.3 years (27&#8211;54).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">60&#8201;mg fluoxetine, 60 days</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Fluoxetine: 11 Placebo: 12</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">3 (tremor)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 (tremor)</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">CSR 050-001<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A12</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Male: 52. Mean age, sertraline: 32.1 years (19&#8211;60). Mean age, placebo: 35.8 years (19&#8211;60).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">10&#8201;mg, 25&#8201;mg, 50&#8201;mg, 75&#8201;mg, 100&#8201;mg, 125&#8201;mg, 150&#8201;mg, 175&#8201;mg, 200&#8201;mg, 250&#8201;mg, 300&#8201;mg, 350&#8201;mg or 400&#8201;mg sertraline, &#8195;1&#8201;day</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Sertraline: 40 (39 were randomised) Placebo: 12 (13 were randomised)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 (mild nervousness) 1 (mild tremor)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 (mild euphoria) 1 (mild tremor)</td></tr><tr><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">CSR 050-201<span style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A13</span></td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Parallel study</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Male: 24. Mean age, 200&#8201;mg sertraline: 25.8 (20&#8211;32). Mean age, 400&#8201;mg sertraline: 27.1 (22&#8211;34). Mean age, placebo: 25.9 (21&#8211;31).</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">200&#8201;mg or 400&#8201;mg sertraline, 14 days</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">Sertraline 200&#8201;mg: 8 Sertraline 400&#8201;mg: 8 Placebo: 8</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">200&#8201;mg: 2 (nervousness, one moderate, one severe) 2 (tremor, one moderate, one unspecified severity) 2 (thinking abnormal, one mild, one moderate) 400&#8201;mg: 2 (nervousness, one mild, one severe) 3 (tremor, two moderate, one unspecified severity) 1 (thinking abnormal, unspecified severity)</td><td rowspan="1" colspan="1" style="padding: 0.2em 0.4em; border: none; vertical-align: top;">1 (moderate nervousness) 2 (thinking abnormal, one mild, one moderate)</td></tr></tbody></table></div><div id="largeobj_idm140000973613984" class="largeobj-link align_right" style="margin-top: 0.692em; text-align: right;"><a target="object" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/table/table3-0141076816666805/?report=objectonly" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Open in a separate window</a></div><div class="tblwrap-foot" style="font-size: 0.8461em; margin: 1.3846em 0px;"><div id="table-fn1-0141076816666805"><p id="__p28" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">CSR: clinical study report.</p></div></div></div><div id="sec4-0141076816666805" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="sec4-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Risk of bias in the included trials</h3><p id="__p29" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Adequate methods for sequence generation and concealment of treatment allocation were described for six trials<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A3&#8211;A6,A8,A11</span>&nbsp;and for concealment of allocation for two trials.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A7,A12</span>&nbsp;The methods were not specified in five trials.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A1,A2,A9,A10,A13</span>&nbsp;Adequate blinding methods were mentioned for seven trials<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A5&#8211;A8,A10&#8211;A12</span>and not specified in six trials.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A1&#8211;A4,A9,A13</span>&nbsp;We did not look at attrition because the subject of our research was side effects, not beneficial effects.</p></div><div id="sec5-0141076816666805" class="sec sec-last" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="sec5-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Meta-analysis</h3><p id="__p30" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Treatment of adult healthy volunteers with antidepressants doubled their risk of harms related to suicidality and violence, odds ratio 1.85 (95% confidence interval 1.11 to 3.08,&nbsp;<em>p</em>&#8201;=&#8201;0.02, I<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">2&#8201;</span>=&#8201;18%) (<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig1-0141076816666805/" target="figure" class="fig-table-link figpopup" rid-figpopup="fig1-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-fig1-0141076816666805" co-legend-rid="lgnd_fig1-0141076816666805" style="display: inline-block !important; zoom: 1 !important; cursor: pointer; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Figure 2</a>). The number needed to treat to harm one healthy person was 16 (95% confidence interval 8 to 100; Mantel-Haenszel risk difference 0.06). Two clinical study reports and one published trial reported the severity of the harms.</p></div></div><div id="sec6-0141076816666805" class="tsec sec" style="clear: both;"><div class="goto jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-container" style="float: right; text-align: right; font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-size: 0.86666em !important;"><a class="tgt_dark page-toc-label jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-heading" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" title="Go to other sections in this page" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="background-image: url(https://static.pubmed.gov/portal/portal3rc.fcgi/4160049/img/2846531); background-color: transparent; padding-right: 17px; margin-right: 3px; color: rgb(100, 42, 143); background-position: 100% 43.5%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat;">Go to:</a></div><h2 class="head no_bottom_margin ui-helper-clearfix" id="sec6-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1.125em; line-height: 1.1111em; margin: 1.125em 0px 0px; color: rgb(152, 87, 53); min-height: 0px; border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(151, 176, 200); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Discussion</h2><p id="__p31" class="p p-first" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">The century-old belief that patients with depression are at heightened risk of suicide as they begin to recover and their energy and motivation return<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr21-0141076816666805" rid="bibr21-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597996" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">21</a></span></span>&nbsp;is being propagated everywhere, e.g. in the 2003 practice guideline from the American Psychiatric Association, which states that ‘clinical observations suggest that there may be an early increase in suicide risk as depressive symptoms begin to lift but before they are fully resolved’.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr22-0141076816666805" rid="bibr22-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">22</a></span></span></p><p id="__p32" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Because of this deeply ingrained idea, many psychiatrists believe that when patients become suicidal on an antidepressant drug, it is not an adverse effect of the drug but a positive sign that the drug starts working.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr7-0141076816666805" rid="bibr7-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">7</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr10-0141076816666805" rid="bibr10-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">10</a></span></span>&nbsp;However, a systematic review from 2009 showed that the research that has been carried out contradicts this belief,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr21-0141076816666805" rid="bibr21-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597981" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">21</a></span></span>&nbsp;and our review also suggests that it is wrong. We found that antidepressants double the risk of suicidality and violence, and it is particularly interesting that the volunteers in the studies we reviewed were healthy adults with no signs of a mental disorder. Our results agree closely with a review of paroxetine trials in both adults and children with mental disorders using regulatory data released after a court case. It included events both during treatment and in the subsequent withdrawal phase and found a doubling in hostility events (odds ratio 2.10, 95% confidence interval 1.27 to 3.48).<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr23-0141076816666805" rid="bibr23-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597989" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">23</a></span></span></p><p id="__p33" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">While it is now generally accepted that antidepressants increase the risk of suicide and violence in children and adolescents<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr5-0141076816666805" rid="bibr5-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597968" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">5</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr12-0141076816666805" rid="bibr12-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597971" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">12</a></span></span>&nbsp;(although many psychiatrists still deny this<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr10-0141076816666805" rid="bibr10-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">10</a></span></span>), most people believe that these drugs are not dangerous for adults. This is a potentially lethal misconception.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr7-0141076816666805" rid="bibr7-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">7</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr10-0141076816666805" rid="bibr10-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">10</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr15-0141076816666805" rid="bibr15-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597990" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">15</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr24-0141076816666805" rid="bibr24-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597974" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">24</a></span></span></p><p id="__p34" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">As far as we know, our review is the first of the risk of suicide and violence in healthy volunteers. It was inspired by David Healy’s work.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr7-0141076816666805" rid="bibr7-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">7</a></span></span>&nbsp;In 2000, Healy published a study he had carried out with 20 healthy volunteers &#8211; all with no history of depression or other mental illness &#8211; and to his big surprise, two of them became suicidal when they received sertraline.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr25-0141076816666805" rid="bibr25-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">25</a></span></span>&nbsp;One was on her way out the door to kill herself in front of a train or a car when a phone call saved her. Both volunteers remained disturbed several months later and seriously questioned the stability of their personalities.</p><p id="__p35" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">In one of the two crossover trials we excluded because we did not have data on the first period separately, a healthy volunteer committed suicide, which was mentioned in both published articles.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A14,A15</span>&nbsp;She had received duloxetine in increasing doses for 16 days, tapered off the maximum dose of 400&#8201;mg daily very quickly (in just four days according to the design of the study) and killed herself four days later while on placebo. The authors, several of whom were employees of Eli Lilly or owned stock in the company, judged her suicide ‘to be unrelated to study drug treatment’,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A15</span>&nbsp;although it is well known that the suicide risk is high when an antidepressant is stopped abruptly.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr10-0141076816666805" rid="bibr10-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">10</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr23-0141076816666805" rid="bibr23-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597993" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">23</a></span></span>&nbsp;There was no more information about the suicide in the articles, and it was not included in the listing of adverse events we acquired from Eli Lilly, which only mentioned a woman who reported suicidal ideation twice while on placebo. As we do not know if this was the same patient, we asked Eli Lilly for access to anonymised data for the volunteer who committed suicide and the detailed person narrative, as we also wanted to know how it could be possible to state that the suicide was not related to duloxetine, but the company refused to give us the data.</p><p id="__p36" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">In another of Eli Lilly’s studies, a healthy 19-year-old student who had taken duloxetine in order to help pay her college tuition hanged herself in a laboratory run by Lilly.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr26-0141076816666805" rid="bibr26-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">26</a></span></span>&nbsp;It turned out that missing in the FDA’s files was any record of the college student and at least four other volunteers known to have committed suicide, and Lilly admitted that it had never made public at least two of those deaths.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr26-0141076816666805" rid="bibr26-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">26</a></span></span></p><p id="__p37" class="p" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">In the other crossover trial we had to exclude, an unknown number of volunteers discontinued paroxetine due to restlessness, tremor and other adverse events.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A16</span>&nbsp;We contacted the corresponding author of the study who referred us to the first author, but despite several attempts of making contact via two different email addresses and phone (to the doctor’s assistant), this author never responded.</p><div id="sec7-0141076816666805" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="sec7-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Exploratory analyses of the clinical study reports</h3><p id="__p38" class="p p-first" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Although only two of the 29 clinical study reports were eligible for our meta-analysis, e.g. as the studies needed to be double-blind, two researchers (AØB and PBD) read them all (2224 pages) and extracted data independently, as we wanted to explore possible selective reporting of harms in the published articles. Nineteen clinical study reports reported on the harms we investigated and nine of these were published, but less than half of the harms were reported in the articles (21 of 50 events on antidepressants and two of four events on placebo).</p><p id="__p39" class="p p-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">One of these studies<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;">A17</span>&nbsp;was mentioned by David Healy<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr7-0141076816666805" rid="bibr7-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">7</a></span></span>&nbsp;who had spoken with the study investigator, Ian Hindmarch. It was a crossover trial of the interaction between sertraline and diazepam that was terminated due to unexpected adverse events after only four days, before the first phase had been completed and before any of the volunteers had received diazepam. All five volunteers in the sertraline group became agitated and four of them anxious, while one of seven volunteers in the placebo group became aggressive, agitated and anxious. The study was never published.</p></div><div id="sec8-0141076816666805" class="sec sec-last" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="sec8-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Limitations</h3><p id="__p40" class="p p-first" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">There can be little doubt that we underestimated the harms of antidepressants. For 11 of our 13 trials, we only had access to the published article, and it well documented that the drug companies underreport seriously the harms of antidepressants related to suicide and violence, either by simply omitting them from the reports, by calling them something else or by committing scientific misconduct.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr2-0141076816666805" rid="bibr2-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_585007452" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">2</a></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr3-0141076816666805" rid="bibr3-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597994" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a></span><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr4-0141076816666805" rid="bibr4-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597979" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a></span>&#8211;<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr5-0141076816666805" rid="bibr5-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597965" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">5</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr7-0141076816666805" rid="bibr7-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">7</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr10-0141076816666805" rid="bibr10-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">10</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr27-0141076816666805" rid="bibr27-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">27</a></span></span>&nbsp;In trials of duloxetine and sertraline, for example, only 33 of 45 cases of suicidal ideation, attempt or injury listed in a trial register were also mentioned in the published reports.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr2-0141076816666805" rid="bibr2-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_585007453" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">2</a></span></span></p><p id="__p41" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Psychiatrists believe that the suicide risk with antidepressants is only increased till age 24, but this misconception builds on seriously flawed trial data that the FDA has published.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr12-0141076816666805" rid="bibr12-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597967" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">12</a></span></span>&nbsp;Several meta-analysts have pointed out just how unreliable the trials are.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr5-0141076816666805" rid="bibr5-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597978" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">5</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr10-0141076816666805" rid="bibr10-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">10</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr28-0141076816666805" rid="bibr28-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597970" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">28</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr29-0141076816666805" rid="bibr29-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597984" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">29</a></span></span>&nbsp;A 2005 meta-analysis conducted by independent researchers of the published trials included 87,650 patients of all ages and found twice as many suicide attempts on drug than on placebo (odds ratio 2.28, 95% CI 1.14 to 4.55).<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr28-0141076816666805" rid="bibr28-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597987" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">28</a></span></span>&nbsp;They also found out that many suicide attempts must have been missing; some of the investigators responded that there were suicide attempts they had not reported in their trials, while others replied that they did not even look for them. Further, events occurring shortly after active treatment was stopped were not counted. Another 2005 meta-analysis conducted by independent researchers used UK drug regulator data and included 40,826 patients; they found a non-significant doubling in suicides or self-harm events when events occurring later than 24 hours after the randomised phase was over were included (relative risk 2.14, 95% confidence interval 0.96 to 4.75, our calculation).<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr29-0141076816666805" rid="bibr29-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597973" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">29</a></span></span>&nbsp;These researchers also noted that the companies had underreported the suicide risk in their trials, and they found that non-fatal self-harm and suicidality were seriously underreported compared to the reported suicides.</p><p id="__p42" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Even the FDA’s 2006 meta-analysis of 100,000 patients in 372 placebo-controlled trials<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr12-0141076816666805" rid="bibr12-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_564597977" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">12</a></span>,<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr30-0141076816666805" rid="bibr30-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">30</a></span></span>&nbsp;is seriously flawed. Based on trials that were included in FDA’s analysis, one of us has estimated that there are likely to have been 15 times more suicides on antidepressant drugs than reported by the FDA.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr10-0141076816666805" rid="bibr10-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">10</a></span></span>&nbsp;Two important reasons for the underreporting of suicides are that the FDA trusted the data the companies sent to them and that they only included events up to 24 hours after the randomised phase was over.<span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><span style="font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em; position: relative; vertical-align: baseline; top: -0.5em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#bibr10-0141076816666805" rid="bibr10-0141076816666805" class=" bibr popnode" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">10</a></span></span></p><p id="__p43" class="p p-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">We did not plan for any sensitivity analyses related to whether the randomisation and blinding methods were adequately described, as we were very well aware before we started our review that in the sort of trials we would find, there would likely be very little or no information about this. We reviewed trials in healthy volunteers, which have a completely different purpose than standard treatment trials, and the drug companies do not have any particular incentive to provide details about how they blinded the drug and the placebo and how they randomised the volunteers in such trials. Furthermore, we studied harms, not clinical beneficial effects, as we included healthy people. It would therefore be inappropriate to assume that trials that did not describe blinding and randomisation methods are less reliable than other trials.</p></div></div><div id="sec9-0141076816666805" class="tsec sec" style="clear: both;"><div class="goto jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-container" style="float: right; text-align: right; font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-size: 0.86666em !important;"><a class="tgt_dark page-toc-label jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-heading" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" title="Go to other sections in this page" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="background-image: url(https://static.pubmed.gov/portal/portal3rc.fcgi/4160049/img/2846531); background-color: transparent; padding-right: 17px; margin-right: 3px; color: rgb(100, 42, 143); background-position: 100% 43.5%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat;">Go to:</a></div><h2 class="head no_bottom_margin ui-helper-clearfix" id="sec9-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1.125em; line-height: 1.1111em; margin: 1.125em 0px 0px; color: rgb(152, 87, 53); min-height: 0px; border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(151, 176, 200); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Conclusions</h2><p id="__p44" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Antidepressants double the occurrence of events in adult healthy volunteers that can lead to suicide and violence. We consider it likely that antidepressants increase suicides at all ages.<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig2-0141076816666805/" target="figure" class="fig-table-link figpopup" rid-figpopup="fig2-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-fig2-0141076816666805" co-legend-rid="lgnd_fig2-0141076816666805" style="display: inline-block !important; zoom: 1 !important; cursor: pointer; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"><span style="position: relative;">&#8203;<span class="figpopup-sensitive-area" style="cursor: pointer; position: absolute; top: 0px; opacity: 0; color: transparent; background-color: transparent; left: -2.5em;">ages.</span></span></a></p><div class="fig iconblock whole_rhythm clearfix" id="fig2-0141076816666805" co-legend-rid="lgnd_fig2-0141076816666805" style="clear: both; margin: 1.3846em 0px; zoom: 1; overflow: hidden; background-color: rgb(255, 252, 240); border: 1px solid rgb(234, 195, 175); border-top-left-radius: 5px; border-top-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-right-radius: 5px; border-bottom-left-radius: 5px; padding: 1.3846em;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig2-0141076816666805/" target="figure" rid-figpopup="fig2-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-fig2-0141076816666805" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a><div data-largeobj="" data-largeobj-link-rid="largeobj_idm140000974062928" class="figure" style="text-align: center; max-height: 80vh; overflow: auto; margin: 0px 0px 1.3846em; padding-top: 12px; padding-right: 12px;"><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig2-0141076816666805/" target="figure" rid-figpopup="fig2-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-fig2-0141076816666805" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"></a><a class="inline_block ts_canvas" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/core/lw/2.0/html/tileshop_pmc/tileshop_pmc_inline.html?title=Click%20on%20image%20to%20zoom&amp;p=PMC3&amp;id=5066537_10.1177_0141076816666805-fig2.jpg" target="tileshopwindow" style="max-width: 100%; border: none; display: inline-block; zoom: 1; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);"><div class="ts_bar small" title="Click on image to zoom" style="background-color: rgb(220, 240, 244); max-width: 100%; margin: auto; position: relative; height: 0px; padding: 0px; color: transparent; font-size: 0.8461em; line-height: 1.6363em;"></div><img alt="An external file that holds a picture, illustration, etc. Object name is 10.1177_0141076816666805-fig2.jpg" title="Click on image to zoom" class="tileshop" src="https://img1.daumcdn.net/relay/cafe/original/?fname=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov%2Fpmc%2Farticles%2FPMC5066537%2Fbin%2F10.1177_0141076816666805-fig2.jpg" style="max-width: 100%; border: 0px; cursor: url(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/corehtml/pmc/css/cursors/zoomin.cur), pointer;"></a></div><div id="largeobj_idm140000974062928" class="largeobj-link align_right" style="margin-top: 0.692em; text-align: right;"><a target="object" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig2-0141076816666805/?report=objectonly" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Open in a separate window</a></div><div class="icnblk_cntnt" id="lgnd_fig2-0141076816666805" style="color: rgb(102, 102, 102); font-size: 0.9em; line-height: 1.5277; display: table-cell; vertical-align: top;"><div style="margin-top: 0px;"><a class="figpopup" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/figure/fig2-0141076816666805/" target="figure" rid-figpopup="fig2-0141076816666805" rid-ob="ob-fig2-0141076816666805" style="display: inline-block !important; zoom: 1 !important; cursor: pointer; color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Figure 2.</a></div><div class="caption" style="margin-bottom: 0px;"><p id="__p45" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Meta-analysis of suicidal or violent events or precursors to such events.</p></div></div></div></div><div id="app1-0141076816666805" class="tsec sec" style="clear: both;"><div class="goto jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-container" style="float: right; text-align: right; font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-size: 0.86666em !important;"><a class="tgt_dark page-toc-label jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-heading" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" title="Go to other sections in this page" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="background-image: url(https://static.pubmed.gov/portal/portal3rc.fcgi/4160049/img/2846531); background-color: transparent; padding-right: 17px; margin-right: 3px; color: rgb(100, 42, 143); background-position: 100% 43.5%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat;">Go to:</a></div><h2 class="head no_bottom_margin ui-helper-clearfix" id="app1-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1.125em; line-height: 1.1111em; margin: 1.125em 0px 0px; color: rgb(152, 87, 53); min-height: 0px; border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(151, 176, 200); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Appendix</h2><div id="sec24-0141076816666805" class="sec sec-first" style="clear: both;"><p id="__p53" class="p p-first" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A1. Pijl H, Koppeschaar HP, Willekens FL, Op de Kamp L, Veldhuis HD and Meinders AE. Effect of serotonin re-uptake inhibition by fluoxetine on body weight and spontaneous food choice in obesity.&nbsp;<em>Int J Obes</em>&nbsp;1991; 15: 237&#8211;242.</p><p id="__p54" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A2. Almeida S, Glahn DC, Argyropoulos SV and Frangou S<em>.</em>&nbsp;Acute citalopram administration may disrupt contextual information processing in healthy males.&nbsp;<em>Eur Psychiatry</em>&nbsp;2010; 25: 87&#8211;91.</p><p id="__p55" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A3. Briscoe VJ, Ertl AC, Tate DB, Dawling S and Davis SN<em>.</em>&nbsp;Effects of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, fluoxetine, on counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia in healthy individuals.&nbsp;<em>Diabetes</em>2008; 57: 2453&#8211;2460.</p><p id="__p56" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A4. Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR, Lee JK, Tracy AP, Wilkinson CW and Price LH<em>.</em>&nbsp;A placebo-controlled study of sertraline’s effect on cortisol response to the dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing hormone test in healthy adults.&nbsp;<em>Psychopharmacology (Berl)</em>&nbsp;2011; 218: 371&#8211;379.</p><p id="__p57" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A5. Chial HJ, Camilleri M, Ferber I, Delgado-Aros S, Burton D, McKinzie S, et&nbsp;al. Effects of venlafaxine, buspirone, and placebo on colonic sensorimotor functions in healthy humans.&nbsp;<em>Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol</em>2003; 1: 211&#8211;218.</p><p id="__p58" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A6. Furlan PM, Kallan MJ, Ten Have T, Pollock BG, Katz I and Lucki I<em>.</em>&nbsp;Cognitive and psychomotor effects of paroxetine and sertraline on healthy elderly volunteers.&nbsp;<em>Am J Geriatr Psychiatry</em>&nbsp;2001; 9: 429&#8211;438.</p><p id="__p59" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A7. Garcia-Leal C, Del-Ben CM, Leal FM, Graeff FG and Guimaraes FS<em>.</em>&nbsp;Escitalopram prolonged fear induced by simulated public speaking and released hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation.&nbsp;<em>J Psychopharmacol</em>&nbsp;2010; 24: 683&#8211;694.</p><p id="__p60" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A8. Knorr U, Vinberg M, Hansen A, Klose M, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Hilsted L, et&nbsp;al. Escitalopram and neuroendocrine response in healthy first-degree relatives to depressed patients &#8211; a randomized placebo-controlled trial.&nbsp;<em>PLoS One</em>&nbsp;2011; 6: e21224.</p><p id="__p61" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A9. Levine LR, Rosenblatt S and Bosomworth J. Use of a serotonin re-uptake inhibitor, fluoxetine, in the treatment of obesity.&nbsp;<em>Int J Obes</em>&nbsp;1987; 11suppl 3: 185&#8211;190.</p><p id="__p62" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A10. Madeo B, Bettica P, Milleri S, Balestrieri A, Granata AR, Carani C, et&nbsp;al. The effects of citalopram and fluoxetine on sexual behavior in healthy men: evidence of delayed ejaculation and unaffected sexual desire. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel group study.&nbsp;<em>J Sex Med</em>2008; 5: 2431&#8211;2441.</p><p id="__p63" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A11. Montejo AL, Deakin JFW, Gaillard R, Harmer C, Meyniel F, Jabourian A, et&nbsp;al. Better sexual acceptability of agomelatine (25 and 50&#8201;mg) compared to escitalopram (20&#8201;mg) in healthy volunteers. A 9-week, placebo-controlled study using the PRSexDQ scale.&nbsp;<em>J Psychopharmacol</em>&nbsp;2015; 29: 1119&#8211;1128.</p><p id="__p64" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A12. Pfizer. Phase 1 single dose titration study to assess the safety and pharmacokinetics of sertraline. Clinical study report: 050-001. 1988.</p><p id="__p65" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A13. Pfizer. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multiple dose study of sertraline in healthy male volunteers. Clinical study report: 050-201. 1988.</p><p id="__p66" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A14. Derby MA, Zhang L, Chappell JC, Gonzales CR, Callaghan JT, Leibowitz M, et&nbsp;al. The effects of supratherapeutic doses of duloxetine on blood pressure and pulse rate.&nbsp;<em>J Cardiovasc Pharmacol</em>&nbsp;2007; 49: 384&#8211;393.</p><p id="__p67" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A15. Zhang L, Chappell J, Gonzales CR, Small D, Knadler MP, Callaghan JT, et&nbsp;al. QT effects of duloxetine at supratherapeutic doses: a placebo and positive controlled study.&nbsp;<em>J Cardiovasc Pharmacol</em>2007; 49: 146&#8211;153.</p><p id="__p68" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A16. Hergovich N, Aigner M, Eichler HG, Entlicher J, Drucker C, Jilma B<em>.</em>&nbsp;Paroxetine decreases platelet serotonin storage and platelet function in human beings.&nbsp;<em>Clin Pharmacol Ther</em>&nbsp;2000; 68: 435&#8211;442.</p><p id="__p69" class="p p-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">A17. Pfizer. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study to assess the effects of sertraline, alone and with diazepam, on psychomotor performance. Clinical study report: 050-206. 1983.</p></div></div><div id="sec17-0141076816666805" class="tsec bk-sec"><div class="goto jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-container" style="float: right; text-align: right; font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-size: 0.86666em !important;"><a class="tgt_dark page-toc-label jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-heading" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" title="Go to other sections in this page" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="background-image: url(https://static.pubmed.gov/portal/portal3rc.fcgi/4160049/img/2846531); background-color: transparent; padding-right: 17px; margin-right: 3px; color: rgb(100, 42, 143); background-position: 100% 43.5%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat;">Go to:</a></div><h2 class="head no_bottom_margin ui-helper-clearfix" id="sec17-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1.125em; line-height: 1.1111em; margin: 1.125em 0px 0px; color: rgb(152, 87, 53); min-height: 0px; border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(151, 176, 200); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Declarations</h2><div id="sec18-0141076816666805" class="sec sec-first" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="sec18-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Competing Interests</h3><p id="__p46" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at&nbsp;<a href="http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf" data-ga-action="click_feat_suppl" ref="reftype=extlink&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CBody&amp;TO=External%7CLink%7CURI" target="_blank" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf</a>(available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no financial relationships with any organisation that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.</p></div><div id="sec19-0141076816666805" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="sec19-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Funding</h3><p id="__p47" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">This study was funded by the Nordic Cochrane Centre, Rigshospitalet. PBD is funded by a scholarship from the University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences. The funding sources had no influence on any part of the study.</p></div><div id="sec20-0141076816666805" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="sec20-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Ethical Approval</h3><p id="__p48" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">No patient consent has been obtained for this study, as it is a systematic review.</p></div><div id="sec21-0141076816666805" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="sec21-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Guarantor</h3><p id="__p49" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">PCG</p></div><div id="sec22-0141076816666805" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="sec22-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Contributorship</h3><p id="__p50" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis; AØB and PCG contributed to the study concept and design and to the acquisition of data; AØB and PBD contributed to searching, screening and extraction of data. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. AØB and PCG contributed to the drafts of the manuscript, and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript for publication. PCG provided administrative and material support and was the study supervisor and guarantor.</p></div><div id="__sec8" class="sec" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="__sec8title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Acknowledgements</h3><p id="__p51" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">The authors thank information specialist Henrik Hornemann from the Copenhagen University Library for assistance in creating search strings in medical databases; Cochrane collaborators from Japan, Maiko Suto, Erika Ota, and Sadequa Shahrook, and China, Zhang Xin, for helping accessing, assessing, translating and interpreting foreign language articles; Justin Northrup and Malcolm Mitchell from Eli Lilly, Joan Korth-Bradley and Chris Gutteridge from Pfizer, and Steven Troy, formerly from Wyeth, for supplying supplemental data. The authors thank our colleagues Tarang Sharma, Emma Maund and Asbjørn Hr&#243;bjartsson for valuable comments and input throughout the project.</p></div><div id="sec23-0141076816666805" class="sec sec-last" style="clear: both;"><h3 id="sec23-0141076816666805title" style="font-size: 1em; line-height: 1.25em; margin: 1.2856em 0px 0.6428em; color: rgb(114, 65, 40); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">Provenance</h3><p id="__p52" class="p p-first-last" style="margin-top: 0.6923em; margin-bottom: 0.6923em;">Not commissioned; previously peer-reviewed at another journal and peer-reviewed for&nbsp;<em>JRSM</em>&nbsp;by Julie Morris.</p></div></div><div id="idm140000972602400" class="tsec sec" style="clear: both;"><div class="goto jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-container" style="float: right; text-align: right; font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-size: 0.86666em !important;"><a class="tgt_dark page-toc-label jig-ncbiinpagenav-goto-heading" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066537/#" title="Go to other sections in this page" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="background-image: url(https://static.pubmed.gov/portal/portal3rc.fcgi/4160049/img/2846531); background-color: transparent; padding-right: 17px; margin-right: 3px; color: rgb(100, 42, 143); background-position: 100% 43.5%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat;">Go to:</a></div><h2 class="head no_bottom_margin ui-helper-clearfix" id="idm140000972602400title" style="font-size: 1.125em; line-height: 1.1111em; margin: 1.125em 0px 0px; color: rgb(152, 87, 53); min-height: 0px; border-bottom-width: 1px; border-bottom-style: solid; border-bottom-color: rgb(151, 176, 200); font-family: arial, helvetica, clean, sans-serif; font-weight: normal;">References</h2><div class="ref-list-sec sec" id="reference-list" style="clear: both;"><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr1-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">1.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Loke YK, Derry S.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Reporting of adverse drug reactions in randomised controlled trials &#8211; a systematic survey</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">BMC Clin Pharmacol</span>&nbsp;2001;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">1</span>: 3&#8211;3.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC57748/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11591227" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=BMC+Clin+Pharmacol&amp;title=Reporting+of+adverse+drug+reactions+in+randomised+controlled+trials+%E2%80%93+a+systematic+survey&amp;author=YK+Loke&amp;author=S+Derry&amp;volume=1&amp;publication_year=2001&amp;pages=3-3&amp;pmid=11591227&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr2-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">2.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Hughes S, Cohen D, Jaggi R.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Differences in reporting serious adverse events in industry sponsored clinical trial registries and journal articles on antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs: a cross-sectional study</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">BMJ Open</span>&nbsp;2014;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">4</span>: e005535&#8211;e005535.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4091397/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25009136" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=BMJ+Open&amp;title=Differences+in+reporting+serious+adverse+events+in+industry+sponsored+clinical+trial+registries+and+journal+articles+on+antidepressant+and+antipsychotic+drugs:+a+cross-sectional+study&amp;author=S+Hughes&amp;author=D+Cohen&amp;author=R+Jaggi&amp;volume=4&amp;publication_year=2014&amp;pages=e005535-e005535&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr3-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">3.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Maund E, Tendal B, Hr&#243;bjartsson A, Jørgensen KJ, Lundh A, Schroll J, et al.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Benefits and harms in clinical trials of duloxetine for treatment of major depressive disorder: comparison of clinical study reports, trial registries, and publications</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">BMJ</span>&nbsp;2014;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">348</span>: g3510&#8211;g3510.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4045316/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24899650" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=BMJ&amp;title=Benefits+and+harms+in+clinical+trials+of+duloxetine+for+treatment+of+major+depressive+disorder:+comparison+of+clinical+study+reports,+trial+registries,+and+publications&amp;author=E+Maund&amp;author=B+Tendal&amp;author=A+Hr%C3%B3bjartsson&amp;author=KJ+J%C3%B8rgensen&amp;author=A+Lundh&amp;volume=348&amp;publication_year=2014&amp;pages=g3510-g3510&amp;pmid=24899650&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr4-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">4.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Maund E, Tendal B, Hr&#243;bjartsson A, Lundh A, Gøtzsche PC.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Coding of adverse events of suicidality in clinical study reports of duloxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorder: descriptive study</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">BMJ</span>2014;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">348</span>: g3555&#8211;g3555.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4045315/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24899651" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=BMJ&amp;title=Coding+of+adverse+events+of+suicidality+in+clinical+study+reports+of+duloxetine+for+the+treatment+of+major+depressive+disorder:+descriptive+study&amp;author=E+Maund&amp;author=B+Tendal&amp;author=A+Hr%C3%B3bjartsson&amp;author=A+Lundh&amp;author=PC+G%C3%B8tzsche&amp;volume=348&amp;publication_year=2014&amp;pages=g3555-g3555&amp;pmid=24899651&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr5-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">5.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Sharma T, Guski LS, Freund N, Gøtzsche PC.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">BMJ</span>&nbsp;2016;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">352</span>: i65&#8211;i65.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4729837/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26819231" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=BMJ&amp;title=Suicidality+and+aggression+during+antidepressant+treatment:+systematic+review+and+meta-analyses+based+on+clinical+study+reports&amp;author=T+Sharma&amp;author=LS+Guski&amp;author=N+Freund&amp;author=PC+G%C3%B8tzsche&amp;volume=352&amp;publication_year=2016&amp;pages=i65-i65&amp;pmid=26819231&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr6-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">6.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Knorr U, Kessing LV.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">The effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in healthy subjects. A systematic review</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Nord J Psychiatry</span>&nbsp;2010;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">64</span>: 153&#8211;163. [<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20088752" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Nord+J+Psychiatry&amp;title=The+effect+of+selective+serotonin+reuptake+inhibitors+in+healthy+subjects.+A+systematic+review&amp;author=U+Knorr&amp;author=LV+Kessing&amp;volume=64&amp;publication_year=2010&amp;pages=153-163&amp;pmid=20088752&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr7-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">7.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Healy D.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Let Them Eat Prozac: The Unhealthy Relationship Between the Pharmaceutical Industry and Depression</span>, New York: New York University Press, 2004.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Let+Them+Eat+Prozac:+The+Unhealthy+Relationship+Between+the+Pharmaceutical+Industry+and+Depression&amp;author=D+Healy&amp;publication_year=2004&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr8-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">8.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Medawar C, Hardon A.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Medicines Out of Control? Antidepressants and the Conspiracy of Goodwill</span>, Netherlands: Aksant Academic Publishers, 2004.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Medicines+Out+of+Control?+Antidepressants+and+the+Conspiracy+of+Goodwill&amp;author=C+Medawar&amp;author=A+Hardon&amp;publication_year=2004&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr9-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">9.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Whitaker R.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Anatomy of an Epidemic</span>, New York: Broadway Paperbacks, 2010.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Anatomy+of+an+Epidemic&amp;author=R+Whitaker&amp;publication_year=2010&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr10-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">10.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Gøtzsche PC.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial</span>, Copenhagen: People’s Press, 2015.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Deadly+Psychiatry+and+Organised+Denial&amp;author=PC+G%C3%B8tzsche&amp;publication_year=2015&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr11-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">11.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Carp J.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">The secret lives of experiments: methods reporting in the fMRI literature</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Neuroimage</span>&nbsp;2012;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">63</span>: 289&#8211;300. [<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22796459" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Neuroimage&amp;title=The+secret+lives+of+experiments:+methods+reporting+in+the+fMRI+literature&amp;author=J+Carp&amp;volume=63&amp;publication_year=2012&amp;pages=289-300&amp;pmid=22796459&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr12-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">12.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Stone M, Laughren T, Jones ML, Levenson M, Holland PC, Hughes A, et al.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in adults: analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug Administration</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">BMJ</span>&nbsp;2009;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">339</span>: b2880&#8211;b2880.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2725270/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19671933" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=BMJ&amp;title=Risk+of+suicidality+in+clinical+trials+of+antidepressants+in+adults:+analysis+of+proprietary+data+submitted+to+US+Food+and+Drug+Administration&amp;author=M+Stone&amp;author=T+Laughren&amp;author=ML+Jones&amp;author=M+Levenson&amp;author=PC+Holland&amp;volume=339&amp;publication_year=2009&amp;pages=b2880-b2880&amp;pmid=19671933&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr13-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">13.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">FDA.&nbsp;<em>Revisions to Product Labeling</em>. See&nbsp;<a href="http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM173233.pdf" data-ga-action="click_feat_suppl" ref="reftype=extlink&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=External%7CLink%7CURI" target="_blank" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM173233.pdf</a>&nbsp;(last checked 2 September 2016).</span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr14-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">14.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Sinclair LI, Christmas DM, Hood SD, Potokar JP, Issac A, Srivastava S, et al.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Antidepressant-induced jitteriness/anxiety syndrome: systematic review</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Br J Psychiatry</span>&nbsp;2009;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">194</span>: 483&#8211;490. [<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19478285" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Br+J+Psychiatry&amp;title=Antidepressant-induced+jitteriness/anxiety+syndrome:+systematic+review&amp;author=LI+Sinclair&amp;author=DM+Christmas&amp;author=SD+Hood&amp;author=JP+Potokar&amp;author=A+Issac&amp;volume=194&amp;publication_year=2009&amp;pages=483-490&amp;pmid=19478285&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr15-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">15.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Moore TJ, Glenmullen J, Furberg CD.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Prescription drugs associated with reports of violence towards others</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">PLoS One</span>&nbsp;2010;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">5</span>: e15337&#8211;e15337.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3002271/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21179515" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=PLoS+One&amp;title=Prescription+drugs+associated+with+reports+of+violence+towards+others&amp;author=TJ+Moore&amp;author=J+Glenmullen&amp;author=CD+Furberg&amp;volume=5&amp;publication_year=2010&amp;pages=e15337-e15337&amp;pmid=21179515&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr16-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">16.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Price J, Cole V, Goodwin GM.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Emotional side-effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: qualitative study</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Br J Psychiatry</span>&nbsp;2009;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">195</span>: 211&#8211;217. [<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19721109" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Br+J+Psychiatry&amp;title=Emotional+side-effects+of+selective+serotonin+reuptake+inhibitors:+qualitative+study&amp;author=J+Price&amp;author=V+Cole&amp;author=GM+Goodwin&amp;volume=195&amp;publication_year=2009&amp;pages=211-217&amp;pmid=19721109&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr17-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">17.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Breggin PR.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Suicidality, violence and mania caused by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): a review and analysis</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Int J Risk Saf Med</span>&nbsp;2003;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">16</span>: 31&#8211;49.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Int+J+Risk+Saf+Med&amp;title=Suicidality,+violence+and+mania+caused+by+selective+serotonin+reuptake+inhibitors+(SSRIs):+a+review+and+analysis&amp;author=PR+Breggin&amp;volume=16&amp;publication_year=2003&amp;pages=31-49&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr18-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">18.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Levin R, Daly RS.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Nightmares and psychotic decompensation: a case study</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Psychiatry</span>&nbsp;1998;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">61</span>: 217&#8211;222. [<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9823031" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Psychiatry&amp;title=Nightmares+and+psychotic+decompensation:+a+case+study&amp;author=R+Levin&amp;author=RS+Daly&amp;volume=61&amp;publication_year=1998&amp;pages=217-222&amp;pmid=9823031&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr19-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">19.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Higgins JP and Green S, eds. Methods for incorporating cross-over trials into a meta-analysis. In:&nbsp;<em>Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions</em>. The Cochrane Collaboration 2011.</span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr20-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">20.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Higgins JPT, Curtin F, Worthington HV, Vail A.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Meta-analyses involving cross-over trials: methodological issues</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Int J Epidemiol</span>&nbsp;2002;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">31</span>: 140&#8211;149. [<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11914310" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Int+J+Epidemiol&amp;title=Meta-analyses+involving+cross-over+trials:+methodological+issues&amp;author=DR+Elbourne&amp;author=DG+Altman&amp;author=JPT+Higgins&amp;author=F+Curtin&amp;author=HV+Worthington&amp;volume=31&amp;publication_year=2002&amp;pages=140-149&amp;pmid=11914310&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr21-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">21.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Mittal V, Brown WA, Shorter E.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Are patients with depression at heightened risk of suicide as they begin to recover?</span>&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Psychiatr Serv</span>&nbsp;2009;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">60</span>: 384&#8211;386.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3712978/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19252052" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Psychiatr+Serv&amp;title=Are+patients+with+depression+at+heightened+risk+of+suicide+as+they+begin+to+recover?&amp;author=V+Mittal&amp;author=WA+Brown&amp;author=E+Shorter&amp;volume=60&amp;publication_year=2009&amp;pages=384-386&amp;pmid=19252052&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr22-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">22.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Jacobs DG, Baldessarini RJ, Conwell Y, Fawcett JA, Horton L and Meltzer H et al. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. American Psychiatric Association, 2003.</span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr23-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">23.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Healy D, Herxheimer A, Menkes DB.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Antidepressants and violence: problems at the interface of medicine and law</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">PLoS Med</span>&nbsp;2006;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">3</span>: e372&#8211;e372.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1564177/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16968128" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=PLoS+Med&amp;title=Antidepressants+and+violence:+problems+at+the+interface+of+medicine+and+law&amp;author=D+Healy&amp;author=A+Herxheimer&amp;author=DB+Menkes&amp;volume=3&amp;publication_year=2006&amp;pages=e372-e372&amp;pmid=16968128&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr24-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">24.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Lucire Y, Crotty C.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Antidepressant-induced akathisia-related homicides associated with diminishing mutations in metabolizing genes of the CYP450 family</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Pharmgenomics Pers Med</span>&nbsp;2011;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">4</span>: 65&#8211;81.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3513220/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23226054" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Pharmgenomics+Pers+Med&amp;title=Antidepressant-induced+akathisia-related+homicides+associated+with+diminishing+mutations+in+metabolizing+genes+of+the+CYP450+family&amp;author=Y+Lucire&amp;author=C+Crotty&amp;volume=4&amp;publication_year=2011&amp;pages=65-81&amp;pmid=23226054&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr25-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">25.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Healy D.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Emergence of antidepressant induced suicidality</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Prim Care Psychiatry</span>&nbsp;2000;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">6</span>: 23&#8211;28.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Prim+Care+Psychiatry&amp;title=Emergence+of+antidepressant+induced+suicidality&amp;author=D+Healy&amp;volume=6&amp;publication_year=2000&amp;pages=23-28&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr26-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">26.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Lenzer J. Drug secrets: What the FDA isn’t telling.&nbsp;<em>Slate</em>&nbsp;2005 September 27,&nbsp;<a href="http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/medical_examiner/2005/09/drug_secrets.html" data-ga-action="click_feat_suppl" ref="reftype=extlink&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=External%7CLink%7CURI" target="_blank" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/medical_examiner/2005/09/drug_secrets.html</a>.</span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr27-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">27.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Medawar C, Herxheimer A.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">A comparison of adverse drug reaction reports from professionals and users, relating to risk of dependence and suicidal behaviour with paroxetine</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">Int J Risk Saf Med</span>&nbsp;2003;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">16</span>: 5&#8211;19.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Int+J+Risk+Saf+Med&amp;title=A+comparison+of+adverse+drug+reaction+reports+from+professionals+and+users,+relating+to+risk+of+dependence+and+suicidal+behaviour+with+paroxetine&amp;author=C+Medawar&amp;author=A+Herxheimer&amp;volume=16&amp;publication_year=2003&amp;pages=5-19&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr28-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">28.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Fergusson D, Doucette S, Glass KC, Shapiro S, Healy P, Hebert P, et al.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Association between suicide attempts and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: systematic review of randomised controlled trials</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">BMJ</span>&nbsp;2005;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">330</span>: 396&#8211;396.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC549110/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15718539" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=BMJ&amp;title=Association+between+suicide+attempts+and+selective+serotonin+reuptake+inhibitors:+systematic+review+of+randomised+controlled+trials&amp;author=D+Fergusson&amp;author=S+Doucette&amp;author=KC+Glass&amp;author=S+Shapiro&amp;author=P+Healy&amp;volume=330&amp;publication_year=2005&amp;pages=396-396&amp;pmid=15718539&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr29-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">29.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D.&nbsp;<span class="ref-title">Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA’s safety review</span>.&nbsp;<span class="ref-journal">BMJ</span>&nbsp;2005;&nbsp;<span class="ref-vol">330</span>: 385&#8211;385.&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a class="int-reflink" href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC549105/" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PMC free article</a>]</span>&nbsp;[<a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15718537" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=pubmed&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Entrez%7CPubMed%7CRecord" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">PubMed</a>]&nbsp;<span class="nowrap" style="white-space: nowrap;">[<a href="https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=BMJ&amp;title=Selective+serotonin+reuptake+inhibitors+(SSRIs)+and+suicide+in+adults:+meta-analysis+of+drug+company+data+from+placebo+controlled,+randomised+controlled+trials+submitted+to+the+MHRA%E2%80%99s+safety+review&amp;author=D+Gunnell&amp;author=J+Saperia&amp;author=D+Ashby&amp;volume=330&amp;publication_year=2005&amp;pages=385-385&amp;pmid=15718537&amp;" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">Google Scholar</a>]</span></span></div><div class="ref-cit-blk half_rhythm" id="bibr30-0141076816666805" style="margin: 0.6923em 0px;">30.&nbsp;<span class="mixed-citation">Laughren TP.&nbsp;<em>Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC)</em>. See&nbsp;<a href="http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/briefing/2006-4272b1-01-FDA.pdf" data-ga-action="click_feat_suppl" ref="reftype=extlink&amp;article-id=5066537&amp;issue-id=277375&amp;journal-id=256&amp;FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&amp;TO=External%7CLink%7CURI" target="_blank" style="color: rgb(100, 42, 143);">www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/briefing/2006-4272b1-01-FDA.pdf</a>&nbsp;(last checked 2 September 2016).</span></div><div><span class="mixed-citation"><br></span></div></div></div></div><p><br></p>