|

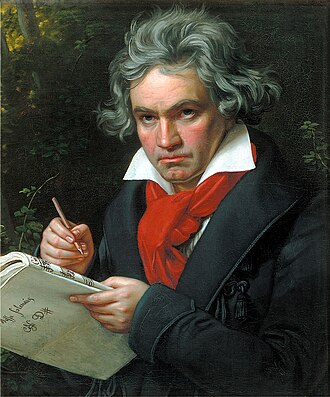

Beethoven |

|

Voices (fourth movement only)

|

Form

The symphony is in four movements, marked as follows:

- Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso (D minor)

- Scherzo: Molto vivace ? Presto (D minor)

- Adagio molto e cantabile ? Andante moderato ? Tempo primo ? Andante moderato ? Adagio ? Lo stesso tempo (B-flat major)

- Recitative: (D minor-D major) (Presto ? Allegro ma non troppo ? Vivace ? Adagio cantabile ? Allegro assai ? Presto: O Freunde) ? Allegro molto assai: Freude, sch?ner G?tterfunken ? Alla marcia ? Allegro assai vivace: Froh, wie seine Sonnen ? Andante maestoso: Seid umschlungen, Millionen! ? Adagio ma non troppo, ma divoto: Ihr, st?rzt nieder ? Allegro energico, sempre ben marcato: (Freude, sch?ner G?tterfunken ? Seid umschlungen, Millionen!) ? Allegro ma non tanto: Freude, Tochter aus Elysium! ? Prestissimo, Maestoso, Molto prestissimo: Seid umschlungen, Millionen!

Beethoven changes the usual pattern of Classical symphonies in placing the scherzo movement before the slow movement (in symphonies, slow movements are usually placed before scherzo[19]). This was the first time that he did this in a symphony, although he had done so in some previous works (including the quartets Op. 18 no. 5, the "Archduke" piano trio Op. 97, the Hammerklavier piano sonata Op. 106). Haydn, too, had used this arrangement in a number of his own works such as the String Quartet No. 30 in E-flat major.================================

1악장: 알레그로 마 논 트로포, 운 포코 마에스토소

‘합창’의 전체 연주시간은 약 70분입니다. 마음먹고 들어야 하는 대곡(大曲)입니다. 1악장은 베토벤의 다른 교향곡들과 달리 매우 흐릿한 느낌으로 시작합니다. A와 E음이 오래도록 지속음으로 울려 나옵니다. 시작부터 이렇게 지속음을 끌고 가는 장면은 훗날 말러의 교향곡 ‘거인’에서도 나타나고, 브루크너의 교향곡에서도 빈번히 등장하지요. 신비하고 몽환적인, 뭔가 불안한 느낌이 감도는 도입부에 이어서 오케스트라가 총주가 매우 단호하고 장대한 느낌의 첫 번째 주제를 연주합니다. ‘빰밤 빰밤’ 하고 터져 나오는 첫 주제, 잘 기억해 두시기 바랍니다.

잠시 경과부를 거친 다음, 드디어 목관이 연주하는 두 번째 주제가 등장합니다. 첫 주제가 장엄하고 생동감 있는 것에 비해 두 번째 주제는 소박하고 정적입니다. 이 두 개의 주제를 염두에 두고 이후에 펼쳐지는 변화에 귀를 기울여보시기 바랍니다. 물론, 아무 생각 없이 음악에 그냥 마음을 맡겨도 좋습니다. 하지만 중요한 것은 첫 번째 주제를 장대한 분위기로 재현하는 마지막 장면까지, 끝까지 들어야 한다는 것!

[Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso. Duration approx. 15 mins.

The first movement is in sonata form, and the mood is often stormy. The opening theme, played pianissimo over string tremolos, so much resembles the sound of an orchestra tuning, many commentators have suggested that was Beethoven's inspiration?but from within that musical limbo emerges a theme of power and clarity that later drives the entire movement. At the outset of the recapitulation section, the theme returns fortissimo in D major, rather than the opening's D minor. The introduction also uses the mediant to tonic relationship, which further distorts the tonic key until, finally, the bassoon plays in its lowest possible register.

The coda employs the chromatic fourth interval.]

2악장: 스케르초. 몰토 비바체

2악장은 1악장의 심각함을 완전히 뒤집는 스케르초 악장입니다. 현악기들이 급작스러운 느낌의 연주로 분위기를 전환하면서 팀파니가 호방하게 막을 올립니다. 이어서 바이올린이 잘게 쪼개지는 듯한 음형들을 다소 빠른 템포로 연주하지요. 그 부분이 주제입니다. 그 주제는 2악장이 끝날 때까지 여러 차례 등장하는데, 팀파니가 옥타브 연타로 거기에 호응합니다.

[Scherzo: Molto vivace ? Presto. Duration approx. 12 mins.

The second movement, a scherzo and trio, is also in D minor, with the introduction bearing a passing resemblance to the opening theme of the first movement, a pattern also found in the Hammerklavier piano sonata, written a few years earlier. At times during the piece, Beethoven specifies one downbeat every three measures?perhaps because of the fast tempo?with the direction ritmo di tre battute ("rhythm of three beats"), and one beat every four measures with the direction ritmo di quattro battute ("rhythm of four beats").

Beethoven had been criticized before for failing to adhere to standard form for his compositions. He used this movement to answer his critics. Normally, a scherzo is in triple time. Beethoven wrote this piece in triple time, but punctuated it in a way that, when coupled with the tempo, makes it sound as if it were in quadruple time.

While adhering to the standard ternary design of a dance movement (scherzo-trio-scherzo, or minuet-trio-minuet), the scherzo section has an elaborate internal structure; it is a complete sonata form. Within this sonata form, the first group of the exposition starts out with a fugue before modulating to C major for the second part. The exposition then repeats before a short development section. The recapitulation further develops the exposition, also containing timpani solos. A new development section leads to the repeat of the recapitulation, and the scherzo concludes with a brief codetta.

The contrasting trio section is in D major and in duple time. The trio is the first time the trombones play in the movement. Following the trio, the second occurrence of the scherzo, unlike the first, plays through without any repetition, after which there is a brief reprise of the trio, and the movement ends with an abrupt coda.]

3악장: 아다지오 몰토 에 칸타빌레

3악장은 철학자 호퍼의 아버지가 “숭고하다”고 말했던 바로 그 악장. 바이올린이 아름다운 선율의 주제를 아련한 느낌으로 연주하면서 시작합니다. 관악기가 메아리처럼 간간히 울려 퍼집니다. 이어서 음악의 템포가 조금 빨라지면서 바이올린과 비올라가 어울려 역시 아름다운 선율의 두 번째 주제를 연주하지요. 이 두 개의 주제를 계속 변주하다가 마침내 우리가 기다려 왔던 4악장, 급격한 느낌의 프레스토 악장으로 들어섭니다.

[Adagio molto e cantabile ? Andante Moderato ? Tempo Primo ? Andante Moderato ? Adagio ? Lo Stesso Tempo. Duration approx. 16 mins.

The lyrical slow movement, in B-flat major, is in a loose variation form, with each pair of variations progressively elaborating the rhythm and melody. The first variation, like the theme, is in 4/4 time, the second in 12/8. The variations are separated by passages in 3/4, the first in D major, the second in G major. The final variation is twice interrupted by episodes in which loud fanfares for the full orchestra are answered by octaves played by the first violins alone. A prominent horn solo is assigned to the fourth player. Trombones are tacet for the movement.]

4악장: 프레스토 - 알레그로 아사이

관악기들의 소란한 음향이 한 차례 울려 퍼지고, 첼로와 베이스가 뭐라고 말을 건네 오는 듯합니다. “자, 지금부터 하는 얘기를 들어보십시요.” 오페라나 오라토리오에 등장하는 해설자의 레치타티보(recitativo)와도 같은 악구입니다. 이어서 그 유명한 ‘환희의 송가’ 테마가 목관에 의해 잠시 나타났다가, 첼로와 베이스, 이어서 현악기 전체, 마지막으로 오케스트라 총주로 점점 확장되면서 얼굴을 드러냅니다.

그리고 드디어 노래가 등장합니다. 베이스(바리톤이 부르기도 함)가 던지는 첫 번째 노랫말, “오 벗이여, 이런 음들이 아니라네! 더 기쁘고 즐거운 노래를 부르세”를 기억해 두시기 바랍니다. 이 가사는 실러의 시에는 등장하지 않습니다. 베토벤이 새롭게 첨가한 노랫말입니다. 합창은 “백만의 사람들이여, 포옹하라! 이 입맞춤을 전 세계에!”라고 노래합니다. 처음부터 끝까지, 시간을 내서 전체 악장을 들어보시길 권합니다. 교향곡 9번의 벅찬 감동을 맛보기 위해서는 당신의 시간과 열정을 투자해야 합니다.

[Presto; Allegro molto assai (Alla marcia); Andante maestoso; Allegro energico, sempre ben marcato. Duration approx. 24 mins.

The famous choral finale is Beethoven's musical representation of Universal Brotherhood. American pianist and music scholar Charles Rosen has characterized it as a symphony within a symphony, played without interruption.[20] This "inner symphony" follows the same overall pattern as the Ninth Symphony as a whole. The scheme is as follows:

- First "movement": theme and variations with slow introduction. The main theme, which first appears in the cellos and basses, is later recapitulated with voices.

- Second "movement": 6/8 scherzo in military style (begins at "Alla marcia," words "Froh, wie seine Sonnen fliegen"), in the "Turkish style"?and concludes with a 6/8 variation of the main theme with chorus.

- Third "movement": slow meditation with a new theme on the text "Seid umschlungen, Millionen!" (begins at "Andante maestoso")

- Fourth "movement": fugato finale on the themes of the first and third "movements" (begins at "Allegro energico")

The movement has a thematic unity, in which every part is based on either the main theme, the "Seid umschlungen" theme, or some combination of the two.

The first "movement within a movement" itself is organized into sections:

- An introduction, which starts with a stormy Presto passage. It then briefly quotes all three of the previous movements in order, each dismissed by the cellos and basses, which then play in an instrumental foreshadowing of the vocal recitative. At the introduction of the main theme, the cellos and basses take it up and play it through.

- The main theme forms the basis of a series of variations for orchestra alone.

- The introduction is then repeated from the Presto passage, this time with the bass soloist singing the recitatives previously suggested by cellos and basses.

- The main theme again undergoes variations, this time for vocal soloists and chorus.[21]

Text of the fourth movement

The text is largely taken from Schiller's "Ode to Joy", with a few additional introductory words written specifically by Beethoven (shown in italics).[22] The text without repeats is shown below, with a translation into English.[23] The score includes many repeats. For the full libretto, including all repetitions, see German Wikisource.[24]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Towards the end of the movement, the choir sings the last four lines of the main theme, concluding with "Alle Menschen", before the soloists sing for one last time the song of joy at a slower tempo. The chorus repeats parts of "Seid umschlungen, Millionen! ...", then quietly sings, "Tochter aus Elysium". And finally, "Freude, sch?ner G?tterfunken, G?tterfunken!"]

Influence

Many later composers of the Romantic period and beyond were influenced specifically by Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.

An important theme in the finale of Johannes Brahms' Symphony No. 1 in C minor is related to the "Ode to Joy" theme from the last movement of Beethoven's Ninth symphony. When this was pointed out to Brahms, he is reputed to have retorted "Any fool can see that!" Brahms's first symphony was, at times, both praised and derided as "Beethoven's Tenth".[45]

The Ninth Symphony influenced the forms that Bruckner used for the movements of his symphonies. Bruckner's Symphony No. 3 is in the same D minor key as Beethoven's 9th and makes substantial use of thematic ideas from it. The colossal slow movement of Bruckner's Symphony No. 7, "as usual", takes the same A?B?A?B?A form as the 3rd movement of Beethoven's symphony, and also uses some figuration from it.[46]

In the opening notes of the third movement of his Symphony No. 9 (The "New World"), Anton?n Dvo??k pays homage to the scherzo of this symphony with his falling fourths and timpani strokes.[47]

Likewise, B?la Bart?k borrows the opening motif of the Scherzo from Beethoven's Ninth symphony to introduce the second movement Scherzo in his own, Four Orchestral Pieces, op. 12.[48][49]

One legend is that the compact disc was deliberately designed to have a 74-minute playing so that it could accommodate Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. Kees Immink, Philips' chief engineer, who developed the CD, recalls that a commercial tug-of-war between the development partners, Sony and Philips, led to a settlement in a neutral 12-cm diameter format. The 1951 performance of the Ninth Symphony conducted by Furtw?ngler was brought forward as the perfect excuse for the change.[50] A Philips news release on 16 August 2007, celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Compact Disc, mentioned the parties?Philips and Sony?extended the Compact Disc capacity to 74 minutes to accommodate a complete performance of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.[51]

In the film The Pervert's Guide to Ideology, the psychanalytical Communist philosopher Slavoj Zizek comments on the use of the Ode use by Nazism, Bolshevism, the Cultural Revolution, the East-West German Olympic team, South Rhodesia, Abimael Guzm?n and the European Union. The beginning of the Ode is an epic music that is easy to infuse with ideology, however the latter part is more personal.[52]

Use as anthem

During the division of Germany in the Cold War, the "Ode to Joy" segment of the symphony was also played in lieu of an anthem at the Olympic Games for the Unified Team of Germany between 1956 and 1968. In 1972, the musical backing (without the words) was adopted as the Anthem of Europe by the Council of Europe and subsequently by the European Communities (now the European Union) in 1985.[53][54] The "Ode to Joy" was used as the national anthem of Rhodesia between 1974 and 1979, as "Rise, O Voices of Rhodesia".[55]

Use as a hymn melody

In 1907, the Presbyterian pastor Henry van Dyke wrote the hymn "Joyful, Joyful, we adore thee"

while staying at Williams College.[56] The hymn is commonly sung in English-language churches to the "Ode to Joy" melody from this symphony.

Year-end's tradition in Japan

The Ninth symphony is traditionally performed throughout Japan at the end of year. In December 2009, for example, there were 55 performances of the symphony by various major orchestras and choirs in Japan.

It was introduced to Japan during World War I by German prisoners held at the Band? prisoner-of-war camp. Japanese orchestras, notably the NHK Symphony Orchestra, began performing the symphony in 1925 and during World War II, the Imperial government promoted performances of the symphony, including on New Year's Eve. In an effort to capitalize on its popularity, orchestras and choruses undergoing economic hard times during Japan's reconstruction, performed the piece at years-end. In the 1960s, these year-end performances of the symphony became more widespread, and included the participation of local choirs and orchestras, firmly establishing a tradition that continues today.

추천음반

2. 페렌츠 프리차이(Ferenc Fricsay)/베를린 필하모닉, 1957. DG. 베를린 필하모닉이 연주한 ‘합창’을 대표하는 지휘자는 물론 카라얀일 것. 하지만 헝가리 태생의 지휘자 페렌츠 프리차이는 카라얀과는 완전히 다른 분위기의 ‘합창’으로 또 하나의 드라마를 남겼다. 말하자면 이 녹음에는 카라얀 이전의 베를린 필하모닉에서 느낄 수 있었던 향취가 담겼다. 게다가 프리차이 특유의 소박하면서도 강인한 음악성, 그가 짧은 생애를 통해 보여줬던 음악적 진정성은 듣는 이의 마음을 온전히 음악에 집중케 한다. 독창진도 좋다. 이름가르트 제프리트(소프라노), 마우렌 포레스터(알토), 에른스트 회플리거(테너), 디트리히 피셔-디스카우(바리톤)가 포진했다.

3. 헤르베르트 폰 카라얀(Herbert von Karajan)/베를린 필하모닉, 1976, DG. 카라얀이 남긴 ‘합창’ 녹음은 여러 편이다. 어느 것이나 들을 만한 연주다. 오늘 추천하는 1976년 리코딩은 독창진이 특히 돋보인다. 안나 토모바 신토프(소프라노), 아그네스 발차(콘트랄토/알토), 페터 슈라이어(테너), 호세 반 담(바리톤)이 포진했다. 카라얀 특유의 섬세하고 유려한 장기가 잘 드러나는 연주일 뿐 아니라, 1980년대의 녹음에 비해 오히려 강렬한 맛이 한층 부각되고 있다. 2악장에서 팀파니가 전해주는 음향적 쾌감, 또 3악장에서 들려주는 선율미도 빼어나다. SACD로도 출시돼 있다.

글 문학수 1961년 강원도 묵호에서 태어났다. 까까머리 중학생 시절에 소위 ‘클래식’이라고 부르는 서양음악을 처음 접했다. 청년 시절에는 음악을 멀리한 적도 있다. 서양음악의 쳇바퀴가 어딘지 모르게 답답하게 느껴졌기 때문이다. 게다가 서구 부르주아 예술에 탐닉한다는 주변의 빈정거림도 한몫을 했다. 1990년대에 접어들면서부터 음악에 대한 불필요한 부담을 다소나마 털어버렸고, 클래식은 물론이고 재즈에도 한동안 빠졌다. 하지만 몸도 마음도 중년으로 접어들면서 재즈에 대한 애호는 점차 사라졌다. 특히 좋아하는 장르는 대편성의 관현악이거나 피아노 독주다. 약간 극과 극의 취향이다. 경향신문에서 문화부장을 두 차례 지냈고, 지금은 다시 취재 현장으로 돌아와 음악담당 선임기자로 일하고 있다. 2013년 2월 철학적 클래식 읽기의 세계로 초대하는 <아다지오 소스테누토>를 출간했다.

출처: 채널예스 칼럼>음악>내 인생의 클래식 101 2013.06.10

http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/22320

출처: 바우의 놀이 마당 원문보기 글쓴이: 바우

![한시와 클래식이 있는 쉼터 [연국 '71]](http://t1.daumcdn.net/cafe_image/cf_img2/img_blank2.gif)