|

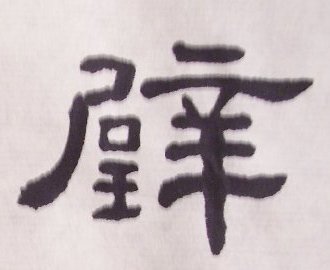

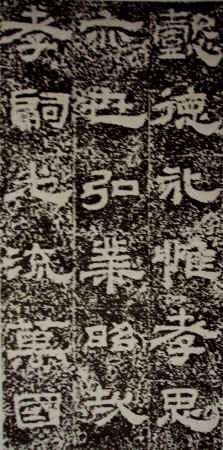

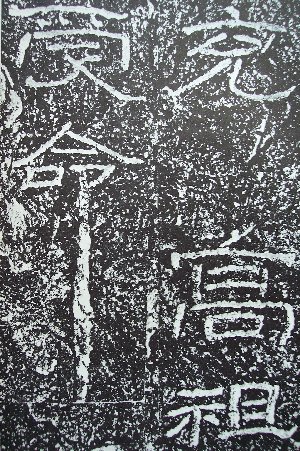

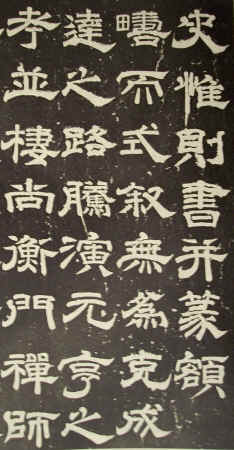

Li Shu germinated in pre-Chin period. During the Chin Dynasty it came to be used by low-ranking officials for more prompt government operations. It simplified the more complicated strokes of Zuan Shu and used a bend instead of making a roundabout turn. This is called Chin Li ( 秦 隸 ) or Old Li ( 古 隸 ). Li Shu is attributed to Cheng Miao ( 程 邈 ) who was a prison official in the Chin Dynasty. The script was used by clerks working in prisons, hence the Chinese term Li Shu ( 隸 書 ) (literally, servitude script). By the Han Dynasty it became popular as a writing style. During the four hundred years history of the Han Dynasty, calligraphers created many beautiful works of Li Shu.

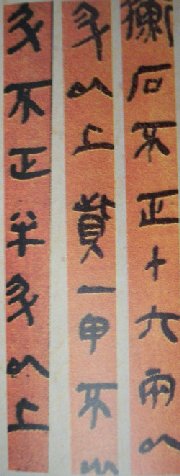

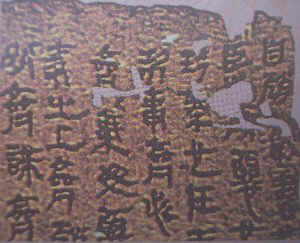

Chin Li on bamboo rolls

Back to TopFeatures of Li ShuThe

structural design of Li Shu is somewhat similar to Zuan Shu. Their

principles focus on the spacing between strokes. The spacing and position of

strokes are well designed to render a sense of elegance and

beauty. Basic features and rules of Li Shu include:

Back to TopEvolution & Changes of Li ShuChinese calligraphy has five major styles: Zuan, Li, Tsao, Hsin and

Kai. The changes and development of styles were also in the above-mentioned

order. In fact, Zuan Shu includes several styles but Li, Tsao, Hsin and Kai are

just referring to a unique style respectively. From the invention of Chinese

characters to the Chin Dynasty, Chinese characters had had drastic revolution

and changes. However, if we compare the characters during this span with those

after the Han Dynasty, differences in characters are found in styles, structure,

strokes as well as the writing method and brushwork. Thus the evolution of Chinese characters

is usually divided into two main periods before or after the Chin

and Han Dynasties. After the Chin and Han Dynasties, the drastic revolution of Chinese characters was focusing on promulgation and convenience. The underlying principles to create a character as set in Zuan Shu were ignored and thus chaos exited for a long time. During this chaos, some characters were written in round shape and others in sharp rectangle shape for the sake of beauty. Only after the Han Dynasty, these ways of writing for beauty’s sake were disappearing eventually. However, because of the Chinese nationality, the revolutionists of characters were gradually forming a new style – the Li Style in search for a higher level of beauty. After the establishment and rise of Li Shu, its use and purpose were greatly different from those of Zuan Shu. During this time, Zuan Shu was used only for import!ant occasions while Li Shu became the common style in daily life. Thus the Li Shu of the Han Dynasty was established. This kind of Li Shu was also the predecessor of Tsao Shu as seen today. We may find the evidence from Li writing on wood rolls ( 木 簡 ). The predecessor of Kai Shu was Hsin Shu, with evidence also found from wood rolls.

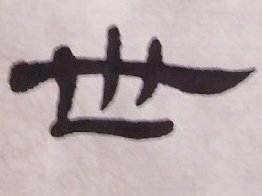

Zhang Chih’s ( 張 芝 ) Tsao Shu retained something of the quality of Li Shu.

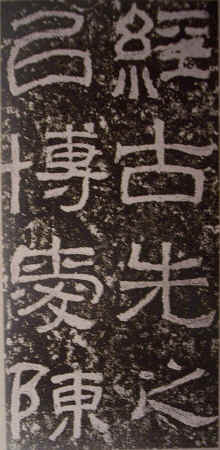

A transitional style on wood rolls resembled mixed Zuan and Li Styles.

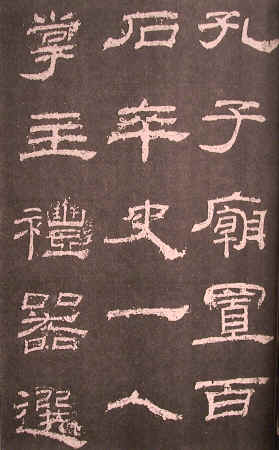

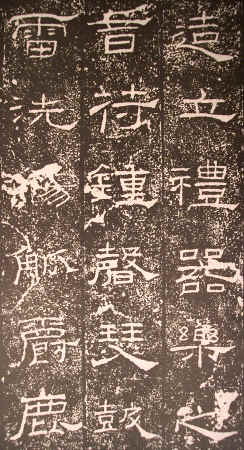

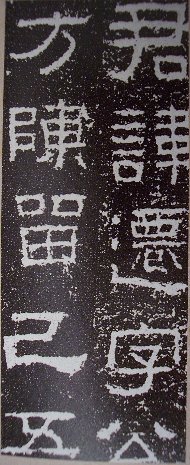

Because of the main writing in the Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms Period was Zuan Shu, Li Shu had experienced numerous refinements and changes. Then it reached its maturity and peak during the later period of the Han Dynasty. This was seen with many tablets in Li Shu.

Back to TopDiscovery of Wood Rolls in Li ShuThe Han

Dynasty and the Three

Kingdoms Period were the intertwined periods for the development of the

Li, Tsao , Hsin, and Kai Styles of calligraphy. They were also the periods that

Chinese calligraphy was reaching its maturity. In the Chin

Dynasty, both Zuan and Li scripts were used but Zuan was used only for

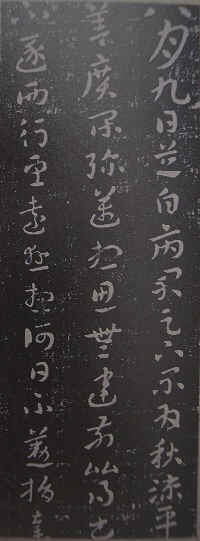

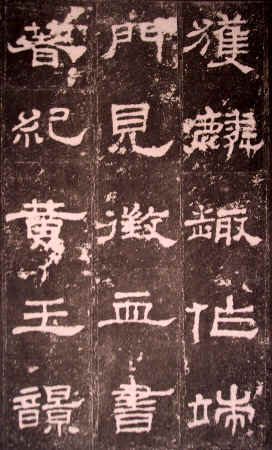

import!ant government operations. In 1901, Aurel Stein led a group of Indian archaeologists and found 40 pieces of wood rolls ( 木 簡 ). They found more than 1000 pieces in their later adventures between 1906 and 1916. The discoveries of the two volumes of Lao Tzu’s “Dao Te Jing” and other works written on wood rolls were showing the transitions from Zuan Shu to Li Shu. The first volume was written in Small Zuan with some Li Shu implication; this was estimated to be a work between 206 to 195 B.C. The second volume was written in Li Shu with some Zuan Shu implication. These evidences give us clues to understand the evolution of Zuan and Li Styles calligraphy during that period. The later Han period was also the time that paper was invented and brush pens were improved. Chinese calligraphy theories were also being published and methods of holding a brush were emphasized. These factors were closely related to the development of Li Shu.

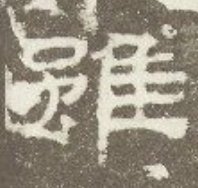

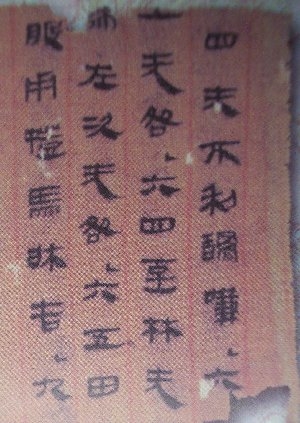

Li

Shu on cloth: I Ching

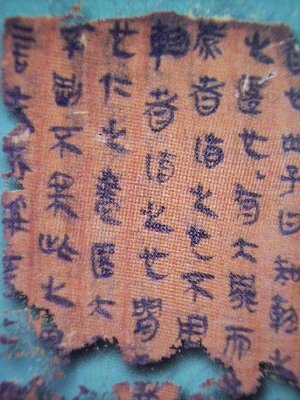

Li Shu on cloth: Dao Te Jing

Back to TopGuide to Start Li ShuA lot of calligraphy teachers agree that students may start learning Chinese calligraphy directly from Li Shu. The basic reason is that it’s easy to learn and grasp the features and it’s can be a preparatory to Zuan Shu or students may learn Kai Shu right after Li Shu. The principles of brushwork are very similar between Li Shu and Zuan Shu. The Center Tip Theory “Zong Fon 中 鋒 理 論 ” (literally, brush pen’s tip in the middle of hairs) as required for Zuan Shu also fits for Li Shu. Remember this is the core of all Chinese calligraphy theories. It was mentioned by every prominent calligrapher. When Yen Jen-Ching stated how his teacher Zhang Shui passed to him the secrets of using a brush, he pointed out that the calligraphy should look like drawing on sand with awl (“Zuei Hwa Sa 錐 劃 沙.”) The principle requires keeping our brush and brush hair as straight and vertical as possible. It’s different from painting or the Western way to hold a pen. According to this principle, we should never ever bend the brush and the hair. We may rotate the brush when necessary with fingertips (knuckles not recommended). Bending a brush outward or toward oneself is a very common defect. By strictly obeying this principle, the hairs (or the sharpness of hairs) of a brush are hiding inside during brush motions rather than going scattered and collapsed.

Please refer to the next section to select a Form Book or work of Li Style to start. Back to TopMasters & Works of Li ShuFamous Tablets in Li Style:

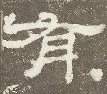

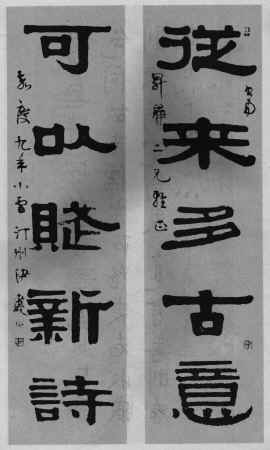

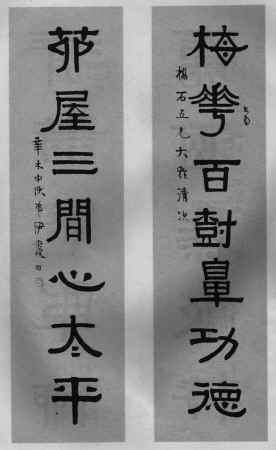

Deng Thu-Ru

(1743-1805)

鄧

石

如 Nicknames: Deng Won-Bai, Deng Won-Bo

His family was poor when he was young and he could not attend school.

He learned calligraphy and seal making from his father and literature from older

men in town. When he was after twenty years old, he earned his living by making

seals. He traveled widely to make friends with scholars. When he was

twenty-seven, a chief lecturer of an academy who appreciated his intellect

referred him to Mae Mio. He was a big collector of ancient calligraphy works

since the Chin and Han Dynasties. While staying at Mae Mio’s house for eight

years, Deng Thu-Ru treasured every moment of his time to practice emulating

ancient calligraphy pieces. He learned Stone Drum Inscriptions “Thu Gu Wen 石

鼓

文

” and Lee

Yang-Bin’s ( 李

陽

冰

) work

and all Li Shu in the Han

Dynasty. Then he began to travel again when Mae Mio was not rich any more. We

he was forty-eight, he visited Beijing but was not satisfied there. He traveled

again and received recognition from other scholars. Because of

his poverty and lack of instruction, his works around age thirty were not highly

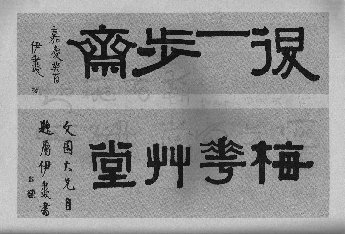

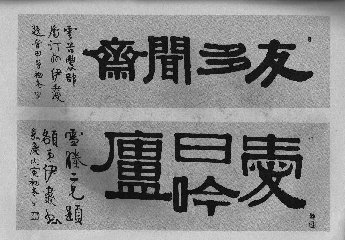

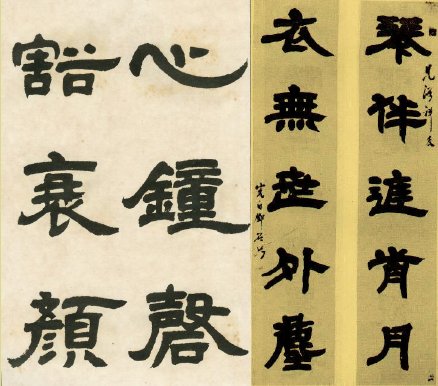

regarded. Yi Bin-So

(1754-1815)

伊

秉

綬 He was peered with Deng Thu-Ru as “South Yi, North Deng.” His works show high level of serenity and strength.

Back to TopVideo Demo of Li Shu

PLEASE CHECK BACK LATER FOR MORE VIDEOS.

Back to TopComparisons of Li StylesPLEASE CHECK BACK LATER.

Back to TopSummary of LearningMost calligraphers agree that beginners may start learning Li Shu as

their first style. The reason is that Li Shu is easy to learn. The student

should choose a Han Dynasty Li Tablet as their first choice. Never try to

emulate Tang Li because Li Shu in the Tang Dynasty was considered loosing the

simplicity, elegance and nature as found in Han Li. A typical Li Shu work in Tang Dynasty lacks depth and delicacy After being familiar with Li Shu, we may proceed to Zuan Shu. It is quite

common that we can refine and edify our Li Shu by practicing more Zuan Shu, or

vise versa. They share some mutual aspects in theory and many great Li Style

calligraphers were also Zuan Style calligraphers.

Back to TopGlossaryBig

Zuan 大

篆

– Characters

in pre-Chin periods. Center Tip Theory 中 鋒 理 論 – Holding a brush vertically but not bent; never let hairs collapse. Chin

Zuan

秦

篆

–

Standardized and simplified Zuan in the Chin Dynasty derived from Big Zuan. Chin Li 秦

隸

(Old Li 古

隸

) – Early Li

Shu as used by the Chin Dynasty prison officials. Han Li 漢

隸

– The Li Shu

in most tablets in the Han Dynasty. They were considered the best Li Style

works. Jade

Ligament Zuan

玉

筋

篆

– Nickname for Small Zuan. Lee

Yang-Bing

李

陽

冰

– Zuan

specialist in the Tang Dynasty. Small

Zuan 小

篆

– As opposed

to Big Zuan; Zuan Shu after Big Zuan. Wood

Rolls 木

簡

– In the Han Dynasty, Li Shu were also written on wood rolls or on

cloth. They sometimes contained some Zuan Shu implication in Li Shu’s strokes

and structures. |

출처: 석산 강창화 원문보기 글쓴이: 영롱한 먹빛

![[정산]이철우](http://t1.daumcdn.net/cafe_image/cf_img2/img_blank2.gif)